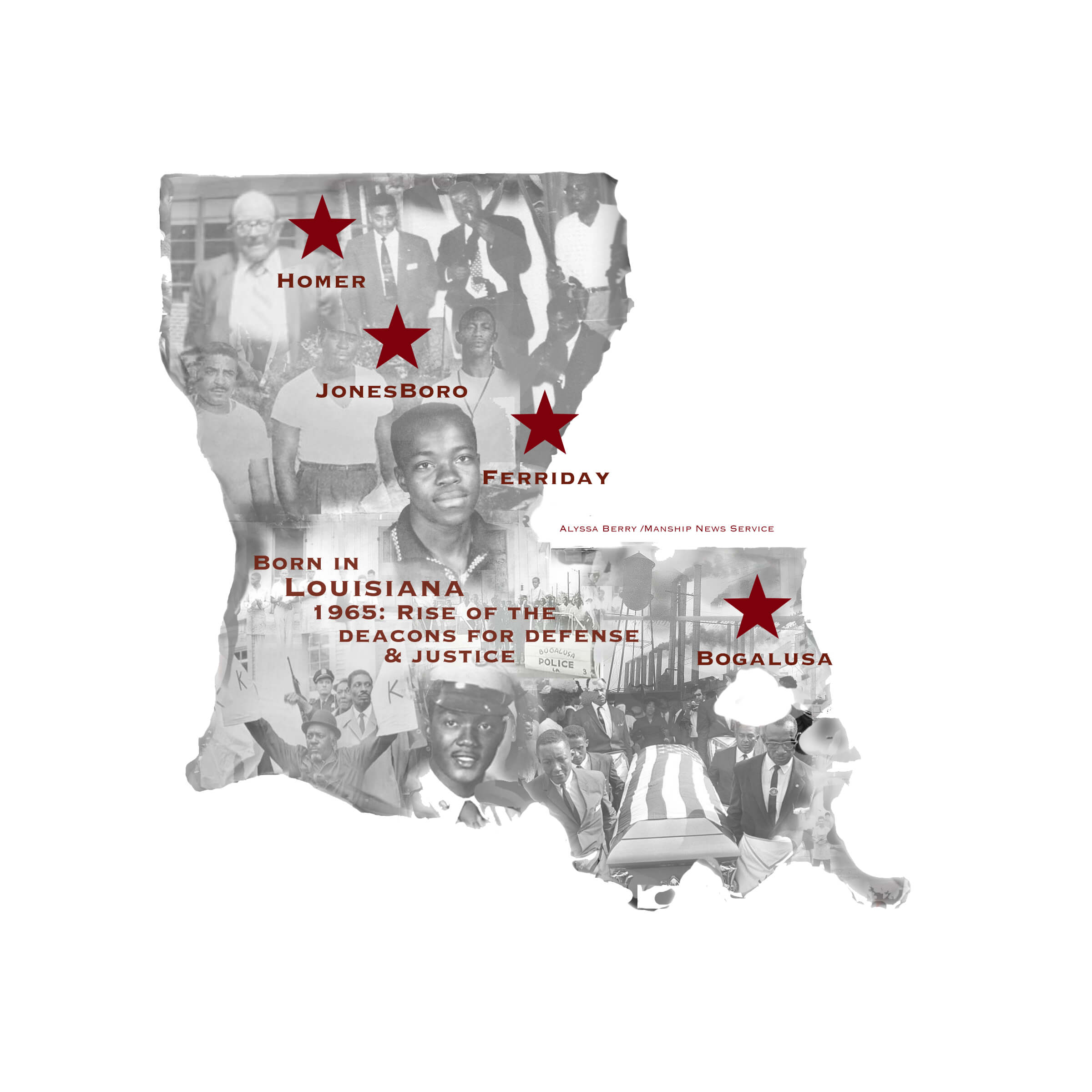

Deacons for Defense & Justice

The Deacons for Defense & Justice was an organization of Black men formed in Louisiana during the Civil Rights-era to protect Black people and neighborhoods, as well as Civil Rights-workers, including white activists, from Ku Klux Klan and police attacks.

Deacons did not provoke violence but stood against it. They were armed and shot back if fired upon.

Deacon chapters were organized in Jonesboro, Bogalusa, Homer and Ferriday before spreading in other forms to other towns.

Once the Deacons felt they had reached their goal of providing protection after major civil rights laws were passed by Congress, implemented and supported by courts, the Deacons slowly ended their work. Most sought neither fame nor gain, but simply saw themselves as filling a need to provide protection and support to those on the front lines in the fight for equality and justice.

Jonesboro

The Deacons’ formation was a direct result of an occurrence in Jonesboro, Louisiana, in July 1964 when approximately 50 cars filled with hooded Klansmen paraded through a Black neighborhood.

“As the Ku Klux Klan motorcade, lit up by the assistant chief of police car in front, paraded through the neighborhood, the intruders jeered and cursed. In their wake, sheets of paper fluttered through the air before settling onto the unpaved road,” the LSU Cold Case Project reported in a four-part series on the Deacons. “Alarmed parents instructed their children to stay inside and away from windows.

“Once the cars moved on, neighbors gathered the litter from the streets. The KKK leaflets threatened retaliation if African-Americans engaged with the Congress of Racial Equality, (CORE), a civil rights group that assisted Black communities with voter registration and integration of public facilities.

“CORE arrived in Jonesboro earlier in this ‘Freedom Summer’ of 1964. The activists busied themselves organizing voter registration drives from within the confines of Black churches. They also joined demonstrations to desegregate public accommodations, such as the restaurants and the community swimming pool. CORE’s presence, as well as the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, moved racial tensions to a new height.

“Alarmed by the motor parade and the threat against CORE, Black residents ran back to their homes to retrieve their shotguns and pistols. Some stayed behind to defend their property, while another group headed to the Freedom House, CORE’s lodging, and stood guard until daylight.”

Although Klansmen did not return that night, the “cold hard facts were clear: If cops were supporting the Klan’s attempt to intimidate Black neighborhoods, the citizens could only rely on themselves for protection.”

The birth of the Deacons in Louisiana “came at a time when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was preaching nonviolent civil disobedience. However, Klan violence against Black neighborhoods in rural areas like Jonesboro was ramping up with frequent cross burnings, arsons, harassment and murder. Armed self-defense seemed like the only option, and the Deacons may have been the first, and certainly became the largest, group in Louisiana to espouse this view.”

The Deacons’ rise is reported in FBI documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act by the LSU Manship School of Mass Communication’s Cold Case Project. The 606-page file had never been released publicly, and it makes clear the Deacon’s intention was never to provoke violence or fire the first shot but just to ward off violence.

A song about the Deacons written by a Deacon Frederick Douglas Kirkpatrick explained that the senseless attacks on Black neighborhoods with the help of police were among the reasons for the rise of the Deacons:

“That is why the Deacons was born,

“To protect our families and our home

“Protect the lives of those that aren’t born

“For decent homes and schools,

“and to fight against Jim Crow Rules

“That is why the Deacons was born.”

Additionally, the lyrics explained:

“Let’s call ourselves the Deacons

“And they will have no fear.

“They’ll think we’re from the church

“… And geez to our surprise, it really worked!”

The Deacons communicated with walkie-talkies and citizen band radios, stood guard during demonstrations and marches, and patrolled Black neighborhoods at night.

A man had to be at least 21 to join the Deacons, have the respect of the Black community and pay dues. The money funded pamphlets, radio equipment, charity donations, and provided Black residents with legal assistance during trials.

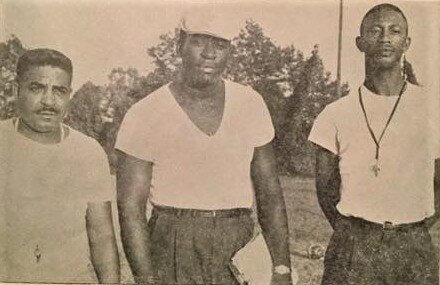

According to FBI records, officers who served the Jonesboro Deacons were Percy Lee Bradford, president; Earnest Thomas, vice president; Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick, secretary; Cosetta Jackson, treasurer; and Allen Scherrah, financial secretary.

Members included Henry Collins Amos, Otis Martin, Olen Satcher, Elton Lee Patterson, Charlie White, Elmo Jacobs, Harvey Barnes, Edd Barnes, Jesse Lewis, Rudolph Patterson, Hose Barnes, W. C. Flanagan, J.B. Bolds, John Jackson, Johnny Bonier, Asper Reed, Frank Bolds, Joseph Doyle, Edgar Joe, Harvey Johnson, the Rev. Sanders Thompson and Army Johnson.

Soon, the Jonesboro Deacons began helping other Louisiana towns where public officials had looked away while the Klan attacked Blacks with impunity.

Bogalusa

In late February 1965, shortly before the Jonesboro Deacons filed formal papers with the Louisiana Secretary of State to become a nonprofit organization, Deacon leaders met with a group of Black men in Bogalusa on establishing a Deacons chapter there, the second of what would become four chapters in Louisiana.

The Deacons were formed in Bogalusa on the evening of Feb. 21, 1965. Ernest “Chilly Willy” Thomas, the vice president of the Deacons’ first chapter in Jonesboro, outlined the goals of this new organization.

At that first meeting, sources told the FBI, “The general tenor of Thomas’ talk was that Negroes should arm themselves, not only for defensive purposes, but that they should have roving patrols so that if a Negro was being arrested by a police officer, other Negroes could come to the aid of the arrested person. Thomas said that if the Ku Klux Klan and white people wanted violence, they ‘intended to combat violence with violence.’”

According to the LSU Cold Case Project, when the FBI learned from a source that the Bogalusa Deacons planned to amass automatic weapons, the bureau became concerned because Bogalusa was a powder keg: “Given the turmoil during marches, counter-marches and Klan attacks, the bureau feared a Deacons chapter in Bogalusa would ignite a war with the Ku Klux Klan.

“Because of this fear, FBI officials instructed agents in Louisiana to ‘immediately initiate an intensive investigation’ of the Deacons ‘because of the potential for violence indicated.’ The bureau ordered its New Orleans field office to be ‘alert for indications of subversive and/or outside influence,’ to determine whether the organization was spreading to other towns and to investigate” one Deacon’s ‘claims that he had weapons contacts in Chicago and Houston.’”

In early 1965, 21-year-old insurance salesman Henry Austan was chased and shot at by Klansmen. There were holes in the driver’s door of his car.

During the spring, he was heading to Bogalusa when he realized that yet again a group of white men was tailing him. He feared they wanted to kill him.

“A couple of times they almost caught me, and I stopped thinking of it as a joke,” Austan told the LSU Cold Case Project. “These people seriously wanted to kill me.”

Tired of being harassed by Klansmen, Austan set a trap the next night.

The LSU Cold Case Project reported:

“Following his usual route, he crossed a wooden bridge, turned down a dirt road and pulled into a pasture behind a line of trees. There, he positioned himself out of sight under the bridge.

“After turning off his headlights, he took out a sawed-off double-barrel shotgun, shells loaded with glass and cardboard, and waited for his pursuers to reach him. When their lights approached, Austan opened fire, surprising the driver. The vehicle swerved, missed the bridge and ran into the water, clearing an escape path for Austan.”

The next day, Austan visited the head of the Deacons chapter in Bogalusa.

“I told him, ‘I can’t collect insurance no more. They’re out to kill me,’” Austan said. ‘I’m going to join the Deacons.’”

Austan became one of the youngest members of the group.

According to the LSU Cold Case Project, tensions boiled over in Washington Parish in June 1965 when two Black deputies were fired upon by Klansmen riding in the bed of a pickup. The driver of the patrol car, Oneal Moore, was killed instantly. His partner, Creed Rogers, survived.

An hour later, the driver of the pickup described by Rogers was arrested before midnight in Tylertown, Miss. Ernest Rayford McElveen was charged with murder by the white sheriff – Dorman Crowe – who had hired the two Black deputies, a move that infuriated Washington Parish Klansmen.

McElveen was never prosecuted, and no other person was ever arrested in the case.

In the wake of the attack, protests grew in Bogalusa.

The LSU Cold Project noted that on July 8, 1965, “the Black community took to the Bogalusa streets to protest Moore’s murder. During the march, an onlooker threw a rock, striking Hattie May Hill, a 16-year-old Black girl, in the back of the head. A mob of white men then blocked Hill’s path to an ambulance.

“Henry Austan was nearby, riding shotgun in Black activist A.Z. Young’s 1964 Cadillac to protect him and help provide an escape if needed. Observing a nurse struggling to help Hill about 50 feet ahead, Austan said he told Deacon Milton Johnson, the driver of Young’s car, to move forward so that Hill and the nurse could get into the car. Johnson then got out of the two-door car to help the nurse get Hill into the back seat. The mob swarmed Johnson, trapping him against the side of the vehicle.

“Austan quickly exited the vehicle and fired a warning shot into the air with his girlfriend’s pistol to try to help Johnson escape.”

But the warning shot “did not deter the mob, and by then, according to newspaper accounts, a white man identified as 26-year-old Alton Crowe of Pearl River began pounding Johnson in his face with his fists. Austan fired a second time, this time with the bullet landing in the chest of Crowe, the married father of five children, who, Austan thought, was trying to enter the vehicle.”

Crowe, though seriously injured, would recover from his wound. Both he and Johnson were charged with aggravated battery.

Contacted by the LSU Cold Case Project, Crowe, no relation to the sheriff, said he believed what he was doing was right at the time as did Austan. He said he had no hard feelings toward Austan.

“We are in a different day and time now than we were back then, and I don’t think the same way I thought back then, so things are a lot different now,” Crowe said, before politely ending the call.

As the cold case reporters noted:

“Austan was never prosecuted, presumably because prosecutors viewed him as defending himself. Without having a weapon for self-defense, Deacon Henry Austan and the others in that car could easily have been killed by the mob. The incident exemplified why the Deacons were needed and why they were armed.”

The day Austan shot Crowe was a turning point. Klansmen saw that the Deacons were not going to allow white supremacists or anyone to attack without fighting back.

Additionally, the cold case project reported:

“In late 1965, Robert ‘Bob’ Hicks, a founder of the Bogalusa Deacons chapter and its original vice president, turned to the court system for help in the workplace, opening job opportunities and promotions that had been unobtainable for African-Americans.

“The Deacons’ efforts helped lead to an enforcement of new civil rights laws that ultimately resulted in Blacks registering to vote in record numbers, gaining power in the political arena and serving routinely in law enforcement in rural Louisiana.”

Austan said the Deacons came into existence “when the situation demanded it. We went out of existence when we were no longer needed.”

Bogalusa Deacons included Charles Sims, president; Royan Burris, vice president; Joseph White, secretary; Andrew Smith, Luke Varnado , Milton Johnson, Elmer “aka Duppie” Barner, Sam Barnes, Bill Crawford, Mizell Butler, O.J. “aka Candy” Nelson), Lemuel Brown, Otha Peters, Theodore Newman, Charles Weary, Henry Austan,, Fletcher Anderson, Robert “Bob” Hicks, Alcie Taylor, Joe Satin, and Reese Perkins; and Joshua Mundy and Harold Ray Mingo, both of Varnado.

Homer

In Claiborne Parish, Frederick Douglass Lewis had been denied the right to register to vote time after time. He had been a good citizen, worked hard, taught Sunday School and helped his community.

All he wanted, he would say later in his life, was to be treated equally and to be afforded all of the rights white citizens enjoyed under the law.

The LSU Cold Case Project reported:

“Because he was not allowed to register to vote, he didn’t have a say in government. He could not serve on the police jury, school board or in the state Legislature.

“After years of frustration, Lewis decided he and his African-American brothers had to do more.”

During the summer of 1965, he and a small number of other Black men secretly formed a Deacons chapter in Homer.

According to the LSU Cold Case Project: “At a voter registration meeting at the Friendship church, munitions worker and longtime parish resident George Dodd discussed the fact local police would not protect Black residents from Klan attacks. He felt the Black community could provide that protection with some organizational help.

“Soon some of the men from Homer talked to friends in Jonesboro, who had created the first Deacons organization. The Jonesboro Deacons assisted Homer in becoming the third town in Louisiana to establish a chapter.

“Organized in June 1965, the Homer Deacons chose Dodd as president and Lewis as vice president. The FBI documents show the group started with 12 members, and a Deacon later told an interviewer from CORE that there may have been as many as 40 members at one time.”

Homer Deacon Lester Green, a grocer, said the Deacons met on Tuesday nights at the Masonic Hall with up to a dozen members attending.

Claiborne Parish Sheriff R.W. Wasson told the FBI that he knew many of the members and that most, including Lewis, were longtime residents who had no records of violence.

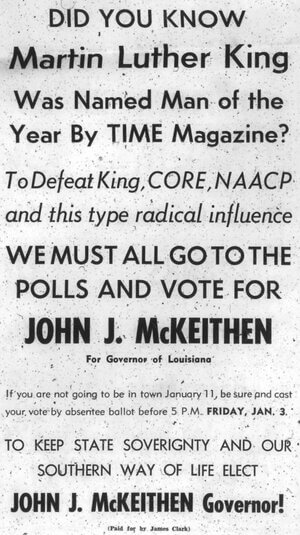

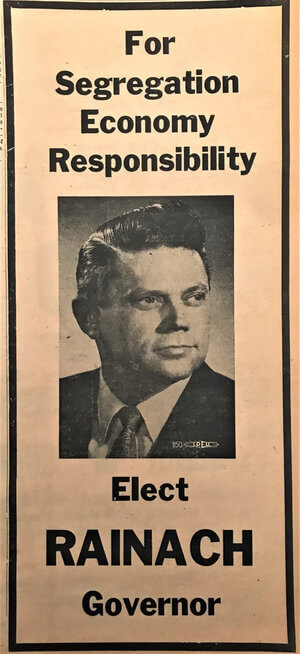

The LSU Cold Case Project reported that Homer “was 17 miles southwest of the Summerfield home of one of Louisiana’s most toxic segregationists, Willie Rainach, who served in the Louisiana Legislature, headed the racist Louisiana Association Citizens’ Councils in 1958 and failed in his bid for governor in 1960. Rainach also led a statewide purge of Black voters from the rolls. Once enforcement of the Civil Rights Bill of 1964 began, Rainach founded the first private school for whites in Claiborne Parish.

“Legislators like Rainach passed laws that made racial segregation legal in every aspect of life. There had long been water fountains in public places marked ‘white’ and ‘colored.’ Students attending Black schools in Claiborne Parish, like those throughout the state, used textbooks handed down from white schools. In many cases, pages were torn out.”

Additionally, cold case students reported: “The Deacons for Defense and Justice in Homer likely would have never been established were it not for the Claiborne Parish Civic League, founded in the 1950s. The league had not gained much momentum until Lewis, the newly elected president, revived it in January of 1965.”

In 1964, only 96 of the 9,755 African-American residents in Claiborne Parish were registered to vote. That changed with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Friendship Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in the early 1960s, became the center for voter registration efforts. There, a Head Start Program for African-American youth was established.

After meeting with civil rights leaders, the parish hired Black policemen while the Claiborne Parish Library was successfully integrated as well as restaurants in the area. Additionally, lawsuits were filed to against local governmental bodies and entities to upend segregation.

According to FBI documents, members of the Deacons for Defense and Justice in Homer included President George Dodd, Vice President Frederick Lewis, Secretary Otis Chatman, Financial Secretary Joe Lester Green, Treasurer Roy Smith, and members Bill Pitts, Emerson Banks, Grant Banks, Napoleon Green, Othar Lewis, Willie James Morris and James Bennett.

Ferriday

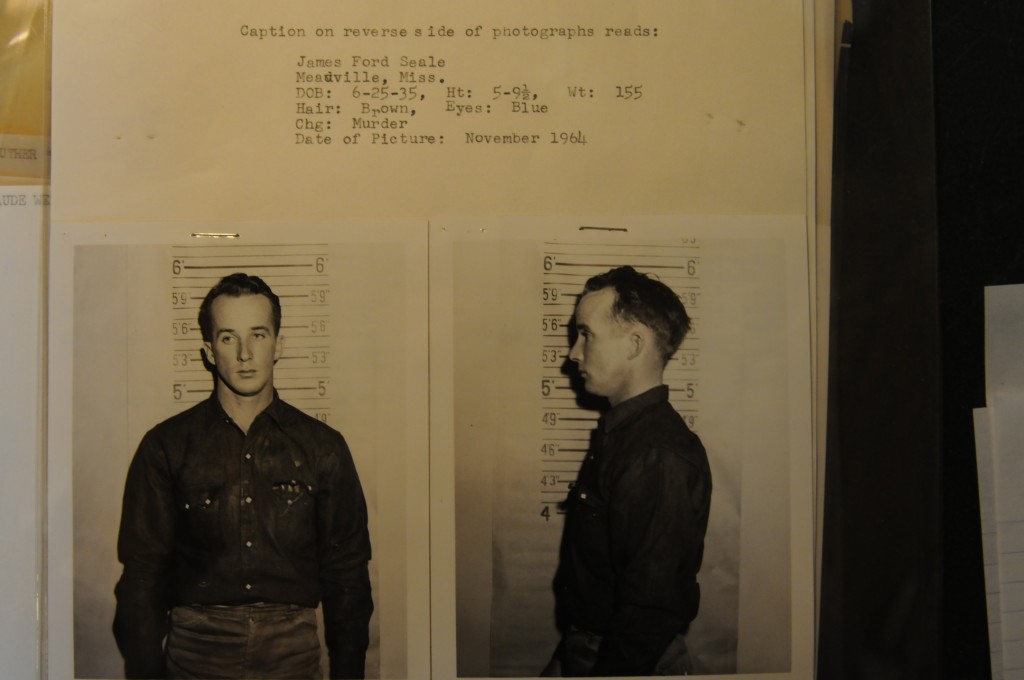

In Ferriday in 1964, Black businessman Frank Morris was killed as a result of the arson of his shoe shop. A popular man in both the Black and white communities, his murder at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan prompted a number of African-American men in town to become active in the Civil Rights Movement.

Morris’ death, and other factors, led to the formation of the Deacons in Ferriday.

According to the LSU Cold Case Project, FBI Agent Don McGorty reported that “the Deacons membership in Ferriday totaled 23. They met weekly and conducted all-night patrols. In addition to each member owning his own weapon, the agent wrote, the unit allegedly possessed three semi-automatic carbines and two walkie-talkies used when patrolling.

“Deacons walked through the Black neighborhood at night armed with weapons in the event of attacks by Klansmen.”

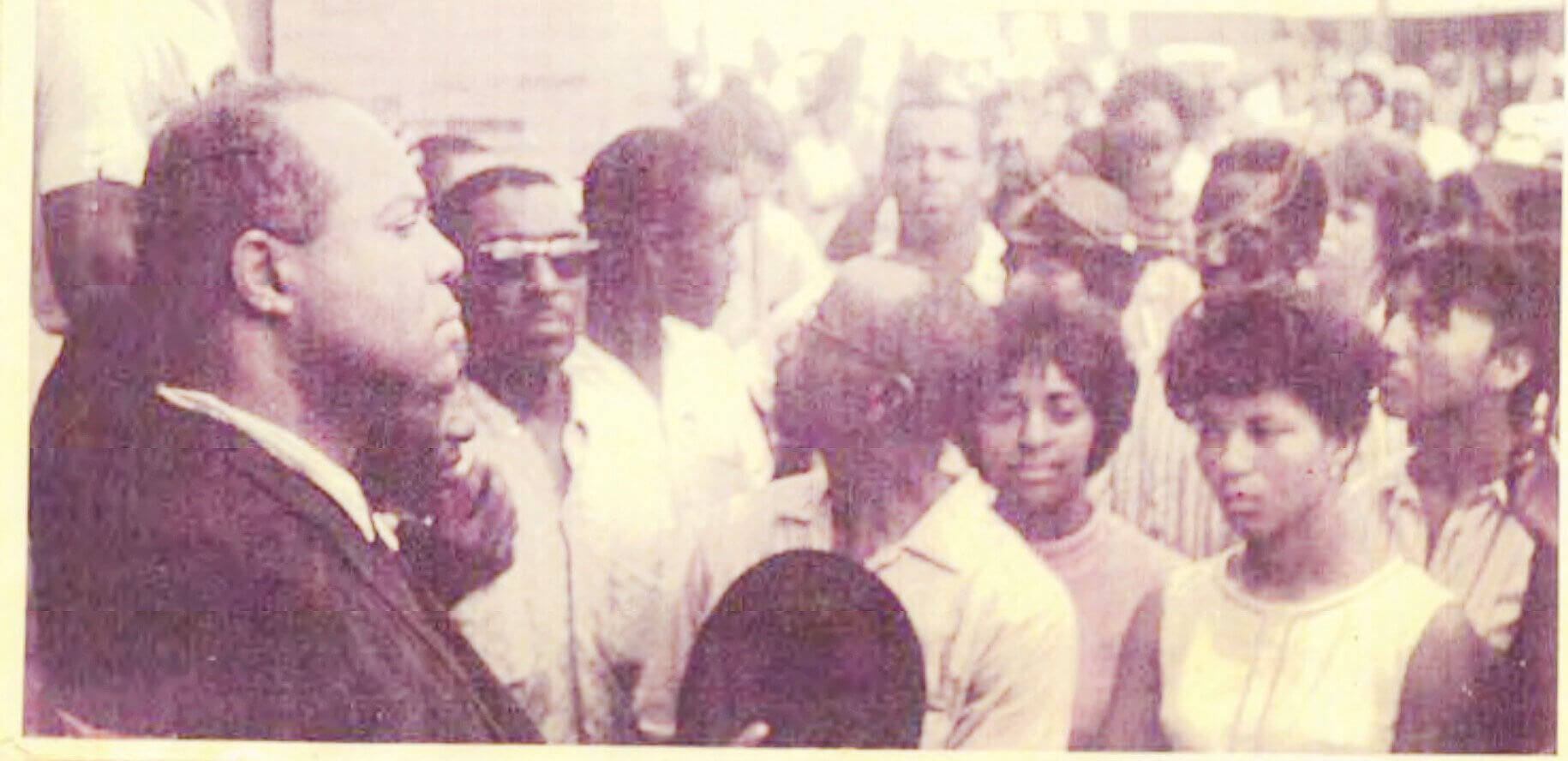

In 1965, representatives of CORE came to Ferriday, deemed an “outlaw town” by the U.S. Justice Department’s head civil rights attorney, John Doar.

CORE members registered Blacks to vote. Their work drew the attention of Klansmen and racist police officers. Two CORE workers – Michael Clurman and Mel Atcheson — were beaten.

Atcheson told the FBI that after this beating, Ferriday resident Victor Graham contacted the Jonesboro Deacons and that a month later, in August 1965, the Ferriday chapter was formed.

Robert Lewis drew inspiration from the sacrifices of the CORE workers. He was moved by the fact that two white men like Atcheson and Clurman took a beating in the name of civil rights.

He decided it was time for him to take a stand, too. He got involved with the CORE-sponsored Ferriday Freedom Movement, which Klansmen soon discovered.

According to the LSU Cold Case Project, in November 1965, Klansmen “sneaked up to his house and threw a gasoline bomb at it. Lewis raced outside with a shotgun. With five children at home, Lewis kept the weapon unloaded. When he saw one of the perpetrators fleeing the scene, he instinctively raised his gun and pulled the trigger, only to hear an empty click.

“Despite the damage the bomb caused to his home and the threat it posed to his family, Lewis was handcuffed by Ferriday police and charged with aggravated assault, according to FBI and CORE documents. Later, he was transported to the parish courthouse jail in Vidalia.

“Lewis later told the Concordia Sentinel that it was a ‘dreaded thing’ for a Black man to be placed into a police car and taken to jail.”

Released after serving two weeks, Lewis now relied on the Deacons to get him home safely.

Among those assisting were David Whatley and Antonne Duncan.

The LSU Cold Case Project reported that Whatley “was among the men inspired by (shoe shop owner Frank) Morris’ life and angered by his murder, and he would become the youngest member” of the Deacons.

One unique feature of the Ferriday Deacons was that they had what Whatley called the “Junior Deacons League,” composed of a half dozen teenagers like him, who were always on call when the older Deacons needed them.

Whatley and Antonne Duncan were part of a Deacon team organized to return Lewis safely to his family. They “knew Klansmen would await Lewis’ release and that deputies would notify the Klan that a Black activist was being released from jail.

“Duncan and a few other young, armed Deacons piled into his brother’s canary yellow Pontiac to rescue Lewis, who also received help from a white bondsman from New Orleans. Had Duncan and the others not rescued Lewis, the police might have dropped him off at the railroad crossing in Vidalia, where Klansmen often waited when Black people were released from the jail.

“Duncan was at the wheel, and when they reached the tracks with Lewis in the car, they bolted past Klansmen waiting there. They quickly gave chase, pursuing the yellow Pontiac for several miles before Duncan watched their headlights start fading away. Soon, Lewis was back in his Ferriday home and reunited with his wife and children.”

There were other attacks on Black men as well.

Deacon Anthony “Lucky” McCraney’s gas station was firebombed, marking the sixth act of racial violence in Ferriday within a two-month period, according to CORE documents.

The home in which two white nuns affiliated with a Catholic church that was headed by a Black priest was firebombed but there were no injuries.

In 1966, David Whatley became the first Black student to integrate Ferriday High. This decision, coupled with his activism, made Whatley a Klan target.

He was arrested and jailed for two weeks on a false claim.

“The main force that we had was marches,” he said. “We’d march on the jail. If they held somebody in there that hadn’t done anything but was falsely accused, we would support them by showing up in court.”

According to the LSU Cold Case Project, the “Deacons held meetings at Mercy Seat Baptist Church, where shoe shop owner Frank Morris had served as an usher, as well as Mount Olive Baptist Church and St. Charles Catholic Church.

“Among the members of the Ferriday Deacons was former Harlem Globetrotter Johnny Lloyd, who was a four-sport coach at the local black school Sevier High, as a Deacon.

“Whatley said it was important for Deacons and activists to demand change in lawful yet effective ways during the civil rights era, and he said that still holds true for the nationwide protests against police abuses today. He said anyone who wants to resolve racial injustices and divisions should do so legally, rather than violently.”

According to FBI documents, Ferriday Deacons included David Whatley, Leo Graham, Victor Graham, Herman Brown, Levado Brown, Richard Thompson, Samuel White, Frank Fleming, James Fleming, Fred Brown, Shine Calhoun, Stafford Redvine, FNU Jones, Anthony “Lucky” McCraney, Simon Smith, Antonne Duncan, Lionel Hooper, Vernon Smith, Anthony White, Joe Davis, Jeffrey Scott, Mack Moore and Johnny Lloyd.

–30—