Robert ‘Shotgun’ Fuller: The 1960 Murder of Albert Pitts Jr., David Lee Pitts, Earnest McFarland and Alfred ‘Monk’ Marshall and Wounding of Charlie Willis

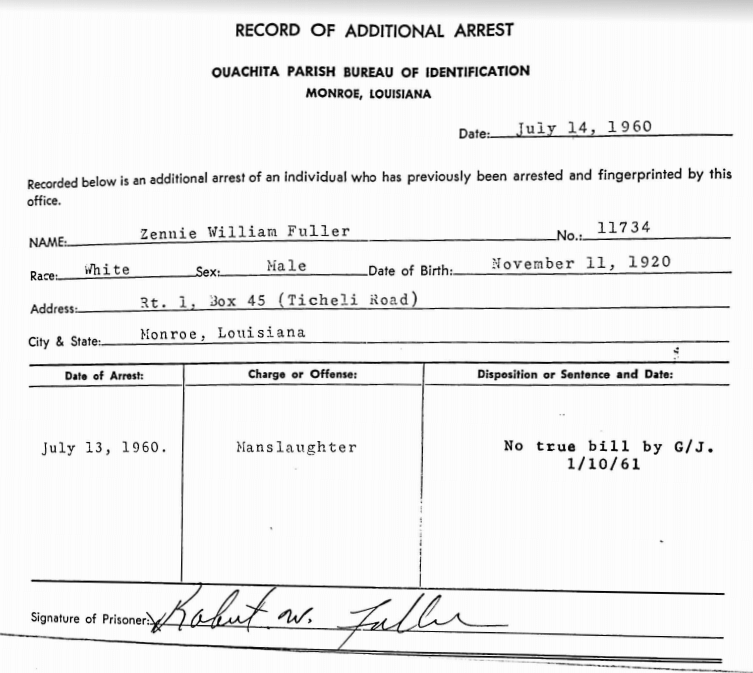

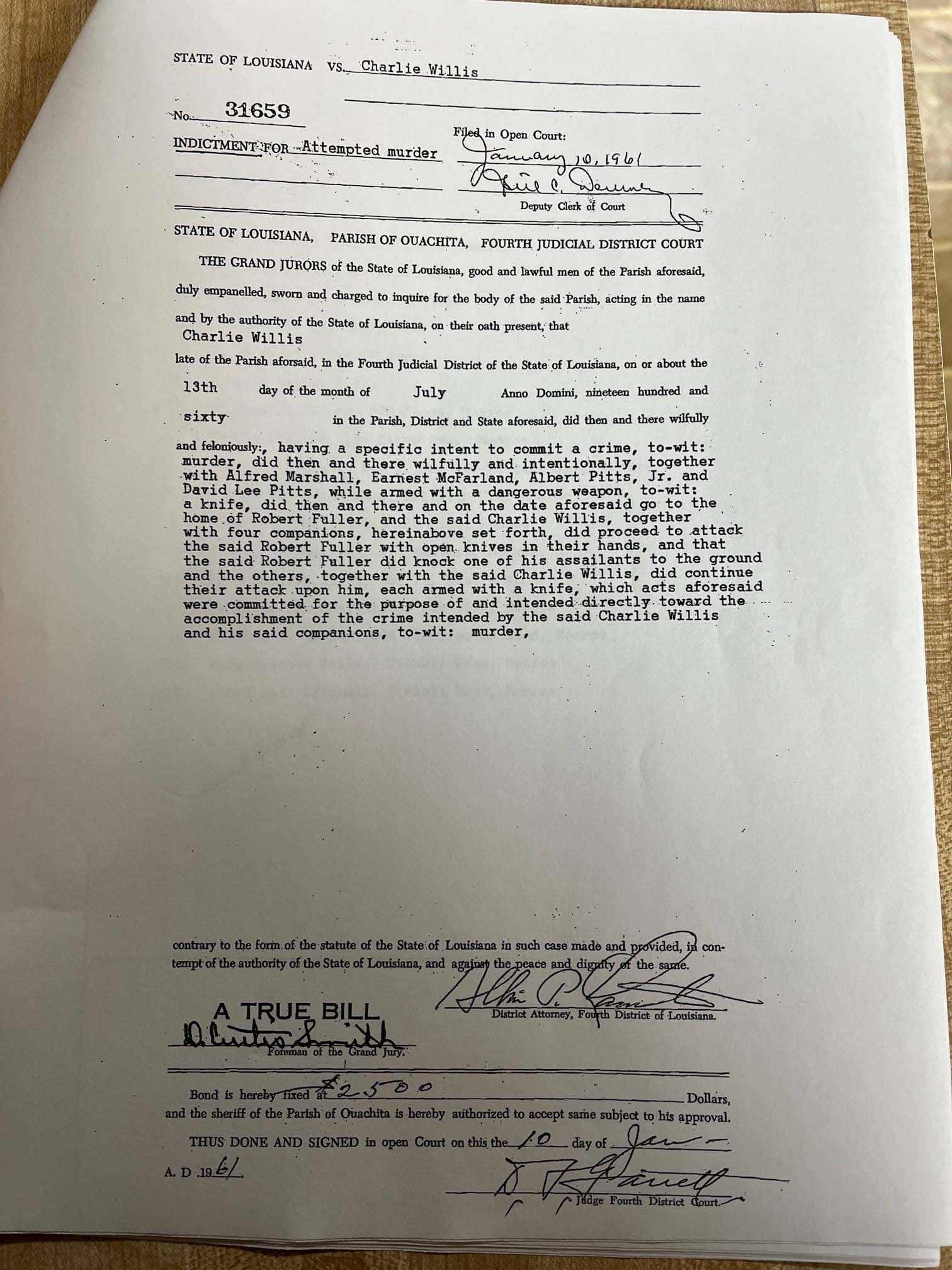

In Monroe, Louisiana, in 1960, Zennie William Fuller, better known as Robert Fuller or Robert “Shotgun” Fuller, shot five of his Black employees killing four and seriously wounding another. An all-white grand jury refused to indict Fuller, choosing instead to indict the lone survivor for the attempted murder of Fuller.

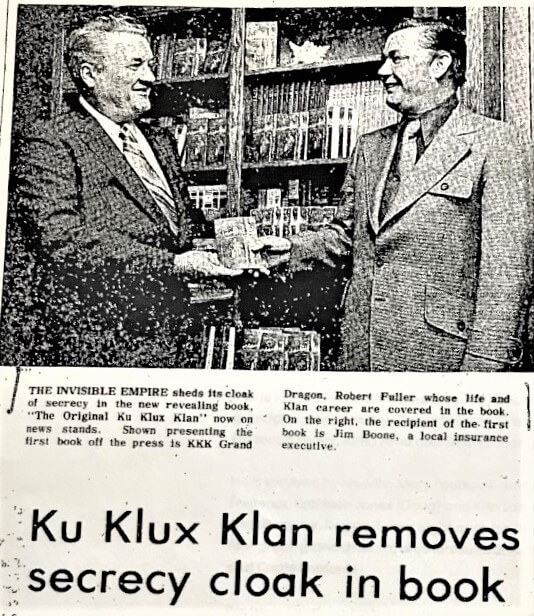

Fuller later became a statewide leader of the Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and served in leadership roles in other Klan groups.

Fuller claimed he acted in self-defense in the shooting, but an investigation by the LSU Cold Case Project discovered witnesses who claimed Fuller admitted to murdering the four men and that one of his sons was involved in the killings. Cold case student reporters also discovered coroner’s reports and grand jury records that the FBI failed to locate during its modern investigation.

Fuller’s Early Life & Diagnosis of Schizophrenia

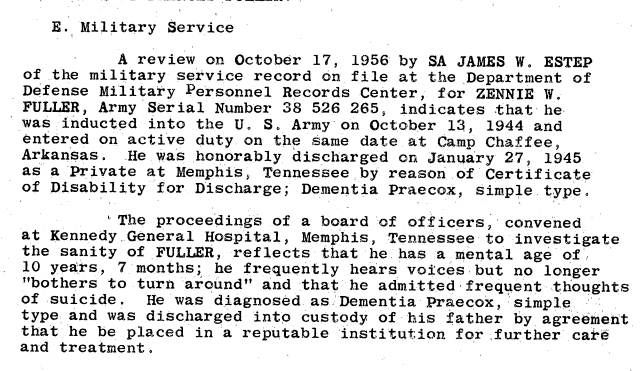

Fuller was born in 1920 in Ouachita Parish, LA. During World War II, he signed up for the draft during World War II. In 1944, he was inducted and entered active duty at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas. Three months later, an Army medical board of officers convened in Memphis, Tennessee, to determine whether Fuller was sane.

The board concluded he suffered from schizophrenia and reported, according to FBI documents, that the private “reflects that he has a mental age of 10 years, 7 months; he frequently hears voices but no longer ‘bothers to turn around’ and that he admitted frequent thoughts of suicide.”

Fuller was honorably discharged into the custody of his father and returned home to Louisiana. The discharge was based on an agreement with Fuller’s father that Fuller be “placed in a reputable institution for further care and treatment.” It is unknown if Fuller ever received medical care for this issue.

1950s: Arrest Record and Threat to FBI Agent’s Wife

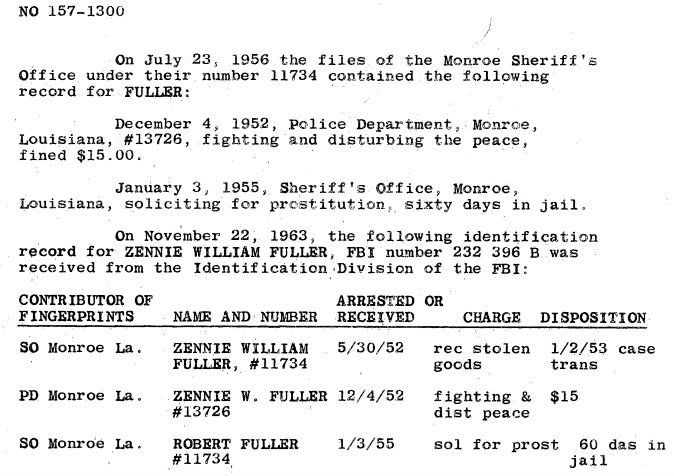

In the 1950s, Fuller was arrested numerous times by the Monroe Police Department and the Ouachita Parish Sheriff’s Office on charges including fighting, disturbing the peace, soliciting for prostitution and receiving stolen goods. Police considered him a violent troublemaker.

He also drew the attention of the FBI and particularly Monroe senior resident agent William Dent, who spearheaded a bureau investigation into Fuller for violations of the White Slave Traffic Act, which forbade the interstate transportation of women or girls for prostitution.

In 1954, Dent’s wife Charlottie received a death threat in a phone call the FBI believed was made by Fuller. Decades later, Charlottie told the Concordia Sentinel that she and the couple’s child were at home alone when the call was made. Her husband was in New Orleans working out of the bureau office there. She said she was told this was the first time a spouse or child of an FBI agent had been threatened in Louisiana.

Fuller was later prosecuted for prostitution in state court, but federal charges were never filed.

During the 1950s, Fuller worked as a logger, a taxi driver and ran a café. He also worked with his father in a business that installed and cleaned out septic tanks.

1960 Shooting in Monroe, Louisiana

By 1960, Fuller was the sole owner of that sanitation service. His work force primarily included young Black men and his oldest son. He had a reputation of paying his Black employees very little and sometimes not at all.

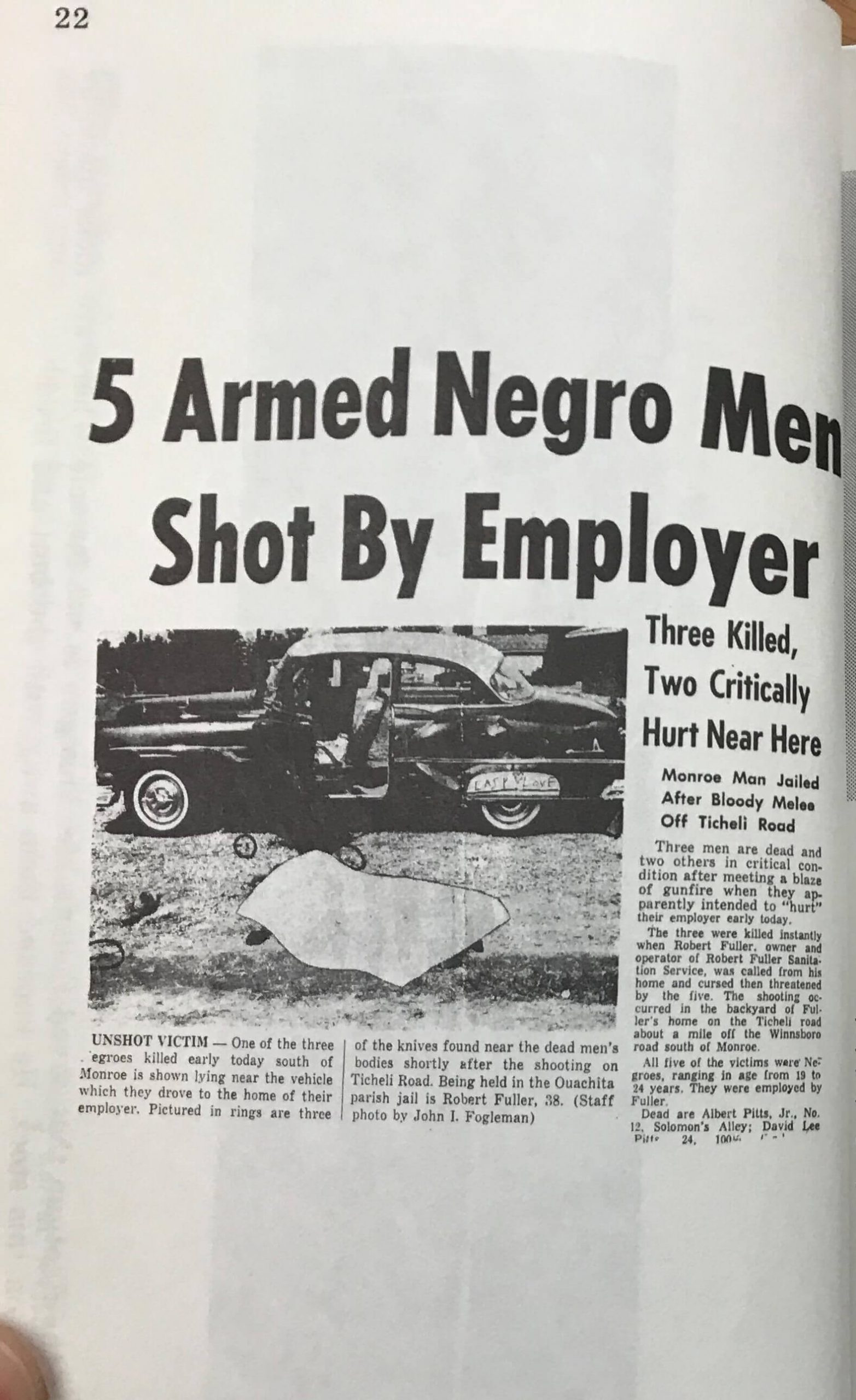

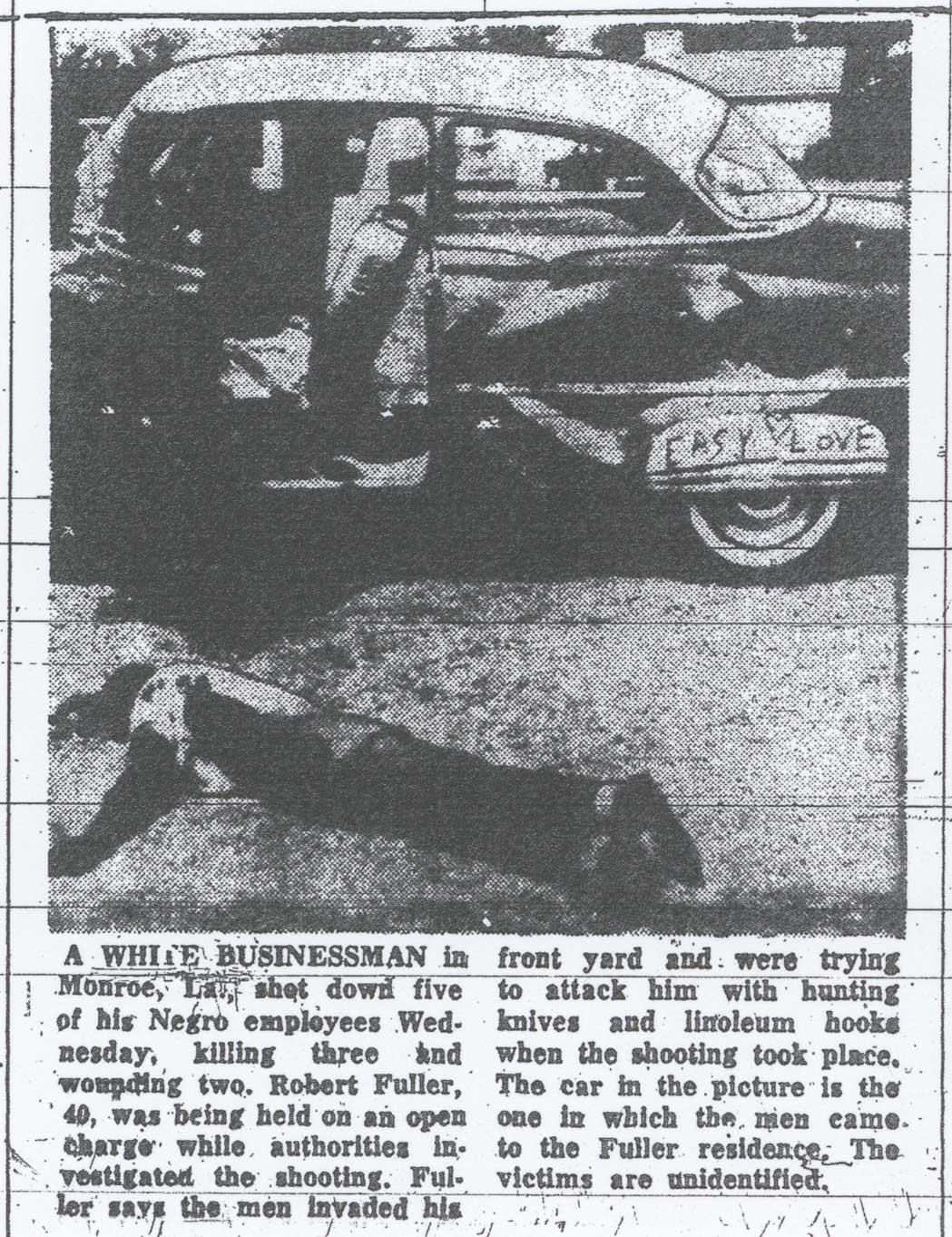

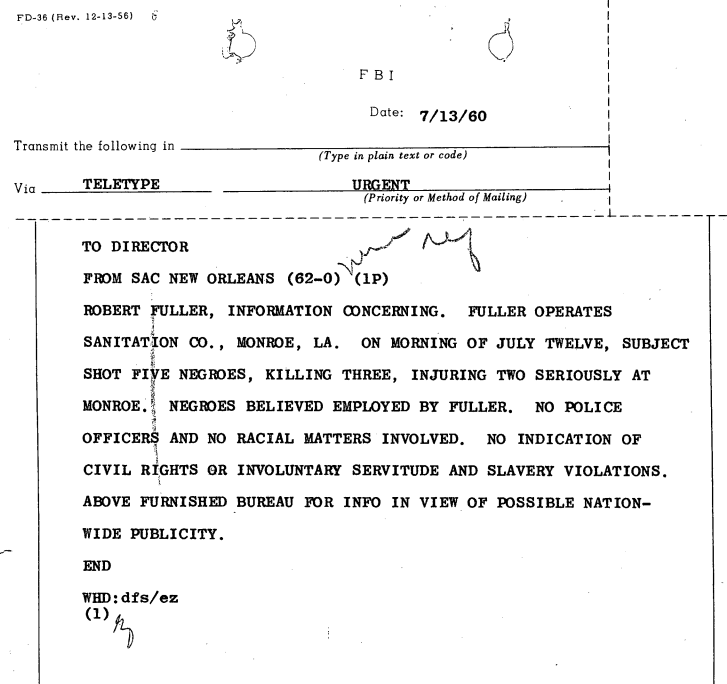

In July, Monroe residents were shocked to read in the morning newspaper that Fuller had shot five of his Black employees, killing three. A fourth died hours later. The story received national coverage in newspapers with Fuller providing the narrative of what he alleged happened.

He told police and reporters that the five men came to his house and charged him with knives. He said he used a double-barrel 12-gauge shotgun to defend himself and made an incredible claim: that he was able to shoot and reload his shotgun three times before the men reached him.

He claimed there had been trouble on a job site the day before and on the day of the shooting he acted in self-defense.

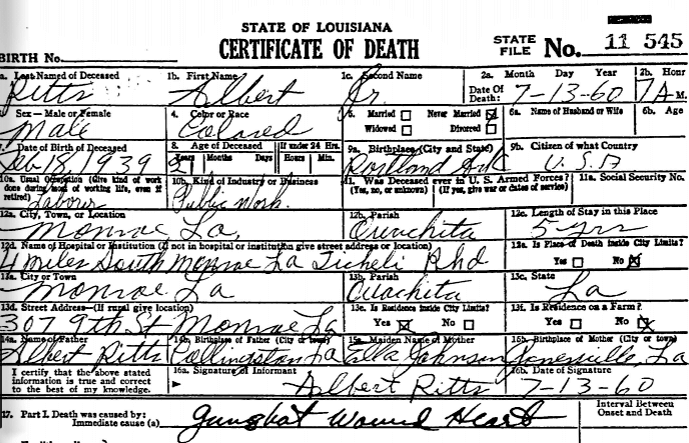

The men shot by Fuller included brothers Albert Pitts Jr., 21, and David Lee Pitts, 24, the youngest of 10 children.

Their cousin, 19-year-old Earnest McFarland, and another worker, Alfred “Monk” Marshall, also died as a result of the shooting.

The lone survivor was Charlie “Cat” Willis, who was the youngest of 12 children in his family.

Newspapers originally named the lone survivor as Willie Gibson, another Black employee of Fuller’s, but later the Monroe daily corrected the error, and noted that Charlie Willis was the only one who lived through the shooting. Gibson was not on the scene of the shooting.

The newspapers also quoted Patricia Sherman, a neighbor of Fuller’s who walked onto the scene in the immediate aftermath. She said she heard the survivor say that the men had come to Fuller’s house that morning to “hurt Mr. Robert.”

Black newspapers reported that there was much more to the story, including that Fuller was notorious for not paying his workers and that the men had gone to Fuller’s house the morning of the shooting to collect what was owed to them.

When police arrived at the scene, knives and linoleum hooks lay beside three of the dead men.

Fuller’s claim of self-defense resonated with the all-white grand jury, which refused to indict him. But a short time later, in a move that stunned everyone, the grand jury indicted the lone survivor, Charlie Willis, for the attempted murder of Robert Fuller.

Due to threats from Fuller on the shooting scene and following the grand jury’s decision not to indict Fuller, Willis opted to plead guilty to the charge against him. He was given five years probation, but later sent to prison for violating the terms of his probation.

Fuller’s Life in the Klan

A few months after the shooting, Fuller became a member of the Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been organized in the Shreveport-Bossier area to fight the Civil Rights Movement and to preserve white supremacy. He also started a local unit of the Original Knights in Monroe as the group’s membership skyrocketed in northern Louisiana and in southeastern Louisiana east of the Mississippi River.

By 1963, Fuller held statewide office as head of the Klan Bureau of Investigation (KBI). Fuller’s primary duty was to organize and approve wrecking projects, where groups of Klansmen went out on violent missions, particularly beatings, arsons and murders, with African-Americans the main targets.

Other targets included civil rights workers, including white ones, as well as any white person who appeared “too friendly” to a Black person. White men who suffered from alcoholism also were beaten in the Klan’s self-proclaimed mission to enforce morality.

Fuller was popular among violent Klansmen, who were both awed and frightened by his claim of singlehandedly fending off five Black men with knives in 1960. As a result, he was given the nickname, “Shotgun.”

He also went around the state visiting local Klan recruits chosen to be members of wrecking crews. He demanded secrecy from them all and threatened death to those who shared those secrets.

During late 1963 and early 1964, Fuller was part of a move to oust Klan leaders J.W. Swenson and Royal Young. He visited klaverns across North Louisiana demanding Klansmen support him and others in a takeover of the Original Knights, ultimately succeeding.

In 1964, Fuller visited the sheriff of Washington Parish, Dorman Crowe, who had recently hired the first two Black deputies in the parish. Fuller demanded that Crowe fire the deputies. The sheriff refused.

Months later, in June of 1965, the two deputies, while on night patrol, were ambushed by Klansmen who fired a rifle and a shotgun from the bed of a pickup. The driver, Oneal Moore, died instantly. His partner, Creed Rogers, survived. No one was ever convicted for the attack.

In 1966, Fuller was subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee investigating the Klan. He claimed in his 1973 self-published book (“The Original Ku Klux Klan”) that the Klan bought him a $150 suit, a $50 pair of alligator shoes and a $100 overcoat for the trip to the hearings in Washington, DC. He also said the Klan gave him $800 in spending money.

There had also been a rumor that Fuller was given $10,000 by Louisiana Governor John J. McKeithen to hold down the violence, but there was little evidence that this occurred.

Fuller appeared before the committee without a lawyer. He refused to answer questions and refused to turn over Klan documents demanded by the committee, claiming to do so would violate his constitutional rights provided by the 1st, 4th, 5th and 14th amendments of the constitution.

While staying in Washington, Fuller also alleged he and another Klansmen slept with the bed against the door to prevent entry to “Negroes who tried to get in.”

Despite his claims of being well-funded for the Washington trip, Fuller said his life was so endangered that he was secluded in his room most of the time and lived on bologna, milk and bread.

His claims had little merit and those who knew Fuller said the book was simply another way for Fuller to make money.

Through the years, Klansmen purged leaders and formed new Klan groups. Fuller rode this tide until the 1970s when he left the Klan to deal with growing financial problems and various legal entanglements.

He died in 1987.

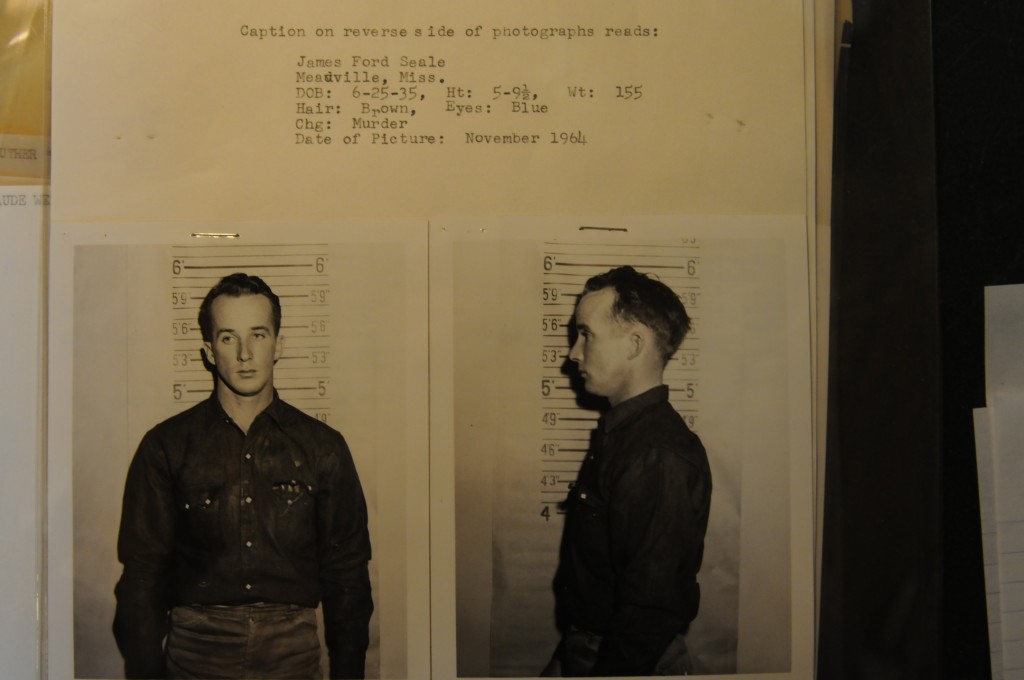

FBI Looks at Case, New Suspect Named

In the fall of 2007, following passage of the Emmitt Till Unsolved Civil Rights Act, the FBI initiated a review of the 1960 murder. The bureau had learned from an unidentified witness that one of Fuller’s sons, William Herbert Fuller, who was 15 in 1960, had been involved in the shooting.

That witness, from Houston, Texas, said that after the men were shot by Fuller that William Herbert Fuller shot four of the Black men in the head. When agents learned that the son had died in 2006, coupled with the fact that Robert Fuller had died in 1987, the bureau closed the case in 2010.

The FBI reported that it had been unable to find any documents from police and court records about the case.

LSU Cold Case Students Investigate the 1960 Shootings

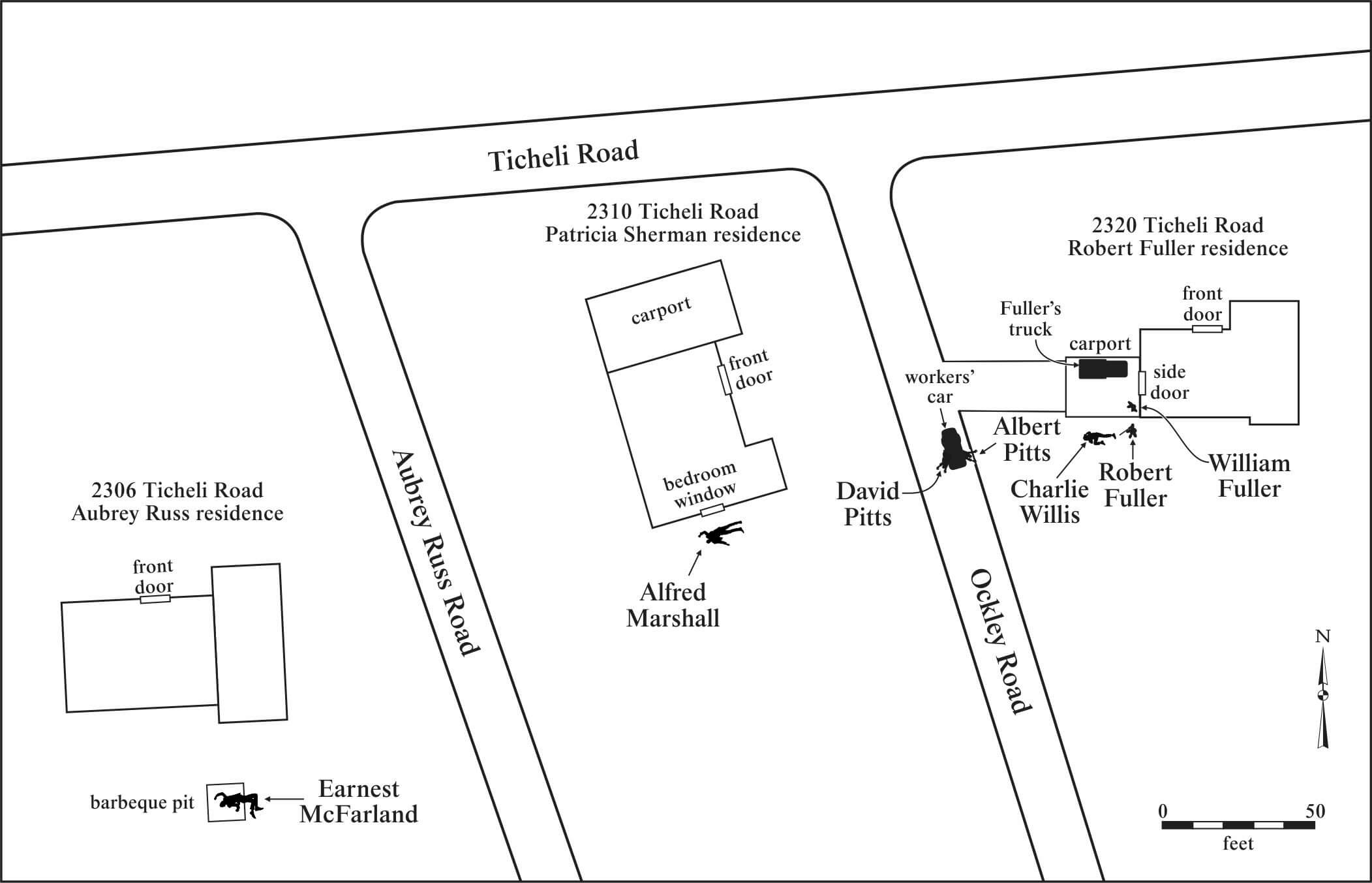

In 2020, students with the LSU Cold Case Project began an investigation into the 1960 killings and reconstructed the crime scene.

Students were able to locate long forgotten coroner reports and other records stored in the basement of the Ouachita Parish Courthouse in Monroe. A librarian provided students with a tip that she had come across the documents while doing other research work years earlier.

These records revealed that Ouachita Parish Coroner Dr. John P. Burton determined the deaths of the three who died at the scene – the Pitts brothers and Marshall — as homicides. But he said the deaths were the result of a fight, although there is no evidence a fight took place.

McFarland died hours later at the hospital.

However, the coroner reports did not describe how many bullets struck the Pitts brothers and Marshall or what type most of the bullets were.

Witness Patricia Sherman Walks onto Crime Scene

After the shootings, Fuller went into his house to call the Ouachita Parish sheriff, Bailey Grant, and report he had shot the men. When Grant and his deputies arrived, local press reports said, they found knives near the bodies and one in the hand of one of the wounded men.

Patricia Sherman, who was 95-years-old when discovered by the cold case reporters, was a neighbor of Fuller’s. She said Fuller was pointing a gun at survivor Charlie Willis’ head when she walked upon the scene. She said Willis was lying on his stomach. He had been shot in the back.

Sherman said Fuller told Willis to tell her why he and the others had come to Fuller’s house that day. She said Willis told her: “We came here to hurt Mr. Robert.”

Willis’ words, spoken with a gun pointed at his head and the bodies of his friends strewn across the lawn, were used by Fuller to bolster his self-defense claim.

Sherman also told an LSU Cold Case reporter that when she saw the bodies on the ground before the police arrived that there were no knives. However, when the police arrived, they found three knives lying beside the bodies, obviously planted by Fuller to back up his self-defense claim.

Weeks later, as the Sherman family prepared to move from the neighborhood to get away from Fuller, she encountered Fuller outside her home. He told her that it was a good thing she had walked onto the scene when she did because she had saved Willis’ life. Otherwise, Fuller said he intended to kill Willis, too.

The Sister of Two Slain Brothers Says Shooting was Ambush

Additionally, LSU student reporters found another witness, who, like Sherman, had never publicly told her story. Willie Mae Sallie, age 94, was the sister of the Pitt brothers – Albert and David Lee. She was also a friend to Willis, the survivor.

Sallie said David Lee told her that the day before the shooting there had been a confrontation on a job site in which one of the men told Fuller he would be reported to the sheriff if he did not pay the men the wages they were owed. Willis told Sallie that later in the day Fuller called David and invited the men to come to his house the next morning to get their money.

Sallie and other witnesses interviewed by the cold case team said as the men were got out of their car Fuller and one of his sons opened fire.

During the publication of the five-part series on the 1960 murder, Sallie gave one final interview in which she told what she recalled about the murder and the aftermath. A day later she was hospitalized with COVID-19. She died the next day.

Two Sons Named William Fuller

In the series on the shooting, the LSU Cold Case Team reported that according to the FBI files, a witness told the bureau in 2007 that “Fuller was seriously behind in paying the men and that he ‘snapped’ when they arrived that morning. An FBI agent noted in one memo that the witness ‘believes that if the men were white, they would not have been killed.’

“The witness described seeing Fuller standing with the shotgun and some of the Black men down on the ground. According to the FBI files, the witness then saw one of Fuller’s sons, 15-year-old William Herbert Fuller, step outside and shoot at least three of the men in the head with a pistol to ‘finish them off.’

“The bureau’s main goal in examining the case was to see if anyone was still alive who might be prosecuted. Robert Fuller died in 1987, and this son, nicknamed Puggy, died in 2005. Given their deaths, an FBI agent noted in a memo in 2010 that there was no one left to prosecute.

”But one other possibility exists. Records show that Robert Fuller had two sons named William, each from a different wife. His eldest son, William Archie ‘Bill’ Fuller, was 19 then and worked in the sanitation business with the Black men.

“Sherman said she saw the 19-year-old standing beside his father when she ran out into the yard right after the shooting, and she suspected he was involved. Moreover, LSU Cold Case Project researchers found a public document at the Ouachita Parish Courthouse that listed the eldest son, William A. Fuller, as a potential witness to the shootings. The document, which listed 16 other names, did not mention his younger brother, Puggy.

“No direct evidence has surfaced linking the eldest son to the shootings, however, and he died in 2016. Local authorities never raised any questions publicly about whether either brother played any role in the shootings, and there is not enough detail in the coroner’s reports to tell if more than one gun was fired that day.”

Apparently unaware of the existence of Bill Fuller, the FBI closed the case in 2010 when Bill Fuller was still alive. He died in 2016.

A Witness Believed Dead Interviewed by Cold Case Reporter

One major mystery previously unsolved was what happened on a job site the day before the shooting. Fuller attributed a threat from employee Willie Gibson as the triggering event. FBI records indicate that a witness told agents that Gibson was dead when the FBI began its review of the case in 2010.

However, Willie Gibson was located by the journalist Ben Greenberg, working on behalf of PBS Frontline.

According to the LSU cold case story on Gibson:

“In 2021, Greenberg put the LSU Cold Case Project in touch with Gibson, who left Monroe the day after the shootings and hitchhiked to New York State.

“Known as ‘Gip’ by his family and friends, Willie Walters Gibson was born and reared in Monroe, the sixth of eight children.”

Gibson had attended elementary school with the five victims of Fuller and had lived in the same neighborhood with them.

According to the LSU cold case investigation:

“The day before the shooting, Gibson was at a job site with Robert Fuller, his son Bill Fuller and the five other young Black workers. Bill Fuller was the only son of Robert Fuller working on the crew, Gibson said, adding that Fuller’s other sons were not old enough to work.

“Gibson said Bill Fuller instructed him to go down into an 8-foot-by-8-foot hole for a septic tank and dig out the excess dirt, something neither he nor his father had ever asked Gibson to do before.

“Gibson was scared, believing he could be buried alive,” and he was claustrophobic.

“He said he complained to Robert Fuller, who told him to follow Bill’s instructions.

“Unhappy with that response, Gibson walked out to the street, where he saw his friends who, minutes earlier, had walked off the job over a separate dispute with the elder Fuller.”

Bill Fuller wanted Gibson to return to work, but Gibson decided to quit, too.

“As he turned to walk away, Gibson said, Bill Fuller suddenly struck him on the left side of his head with a shovel, knocking Gibson to the ground.

“Bill Fuller tried to hit Gibson again and missed as Gibson rolled away.”

Gibson feared the Fullers were going to kill him.

“Gibson said he jumped up and ran only to be chased by Bill Fuller, who insisted that he return to work. Gibson kept running, blood dripping down his face, until he caught up with his friends.”

When word came that Fuller wanted the men to come to his home for their pay the next day, Gibson refused to go and pleaded with the others not to either. He feared it was a trap.

“That man is crazy,” Gibson said of Fuller.

Fuller had claimed to police that Gibson had attempted to hit him with a shovel and had cursed him. He even claimed that Gibson had been arrested earlier for hitting a white man with a brick. The press ran his accusations without checking them out.

The LSU Cold Case Project learned that Fuller’s story was a lie and that Gibson had never been arrested.

The day after the shooting, on his father’s advice, Gibson left Monroe for fear of his life. With $12 in his pocket, he hitchhiked to New York City where his brother and sister came to get him and took him back to their home in Rochester, New York. Gibson has lived there ever since.

Months later, Gibson returned to Monroe, where his old friend Charlie Willis came to visit him at the home of Gibson’s parents. Willis told Gibson about the ambush.

According to the LSU Cold Case investigation story, “The FBI closed the case in 2010, noting that both Robert Fuller and the younger son named by the informant were already dead. But Bill Fuller, who was never charged with any crime, was still alive. He died in 2016.”

Gibson said he cannot forget what happened despite the passage of years.

“I think about it all the time. It goes through my mind all the time when they killed all my boys. Just shot them down for no reason.

“That’s what they did. Shot them all down like they were pigeons flying in the air, and they had did nothing.”

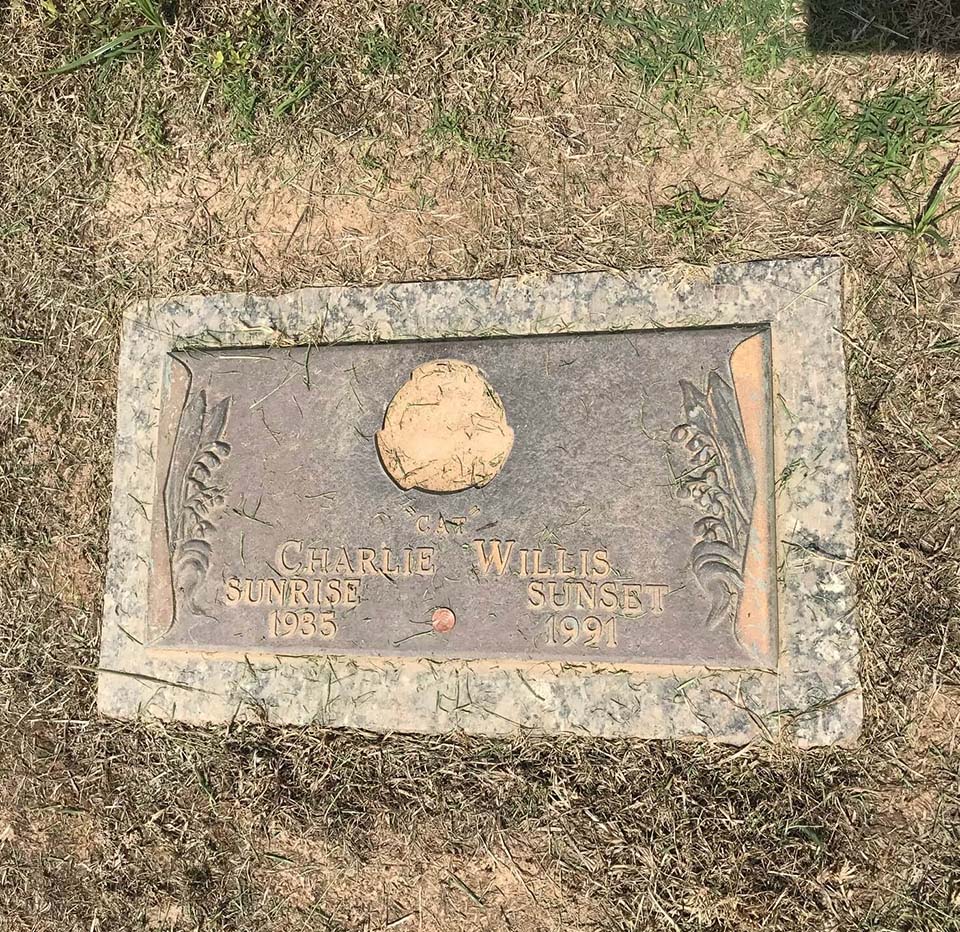

Shooting Survivor Charlie ‘Cat’ Willis died in 1991

Few men lived with injustice as long as Charlie Willis, the lone survivor of the shooting.

According to the LSU Cold Case Project:

“On the same day that the grand jury declined to indict Robert Fuller, it indicted the wounded survivor, Charlie Willis, on a charge of attempting to murder Fuller.

“Ouachita Parish District Judge Jesse Heard set Willis’ bail at $2,500. Sheriff Bailey Grant then detained Willis in the parish jail because he could not make bail.

“Three and a half months later, on April 25, 1961, Willis returned to the courthouse and changed his plea to guilty.

“No record of the court proceedings in the case – ‘State of Louisiana vs. Charlie Willis’ – exists, although 17 possible witnesses were named in a court document.

“The proceedings did not last more than a day. Judge Heard gave Willis a five-year suspended sentence with probation based on good behavior.

“After his court hearing, Willis went to live with his older sister, who had reared him, after their parents died, on a farm on the outskirts of Monroe. Within months, Willis moved to Monroe and worked in construction.

“Four years later, a year before his probation was set to end, Heard issued a warrant for Willis’ arrest for a probation violation. The court documents state that Willis had left the state without permission.

“On June 10, 1966, the court revoked Willis’ probation and sent him to the Louisiana Correctional & Industrial School in DeQuincy, Louisiana, some 200 miles away.”

Willis died in 1991, 31 years after the shooting. For the rest of his life, he suffered chronic back pain due to the gunshot wound.

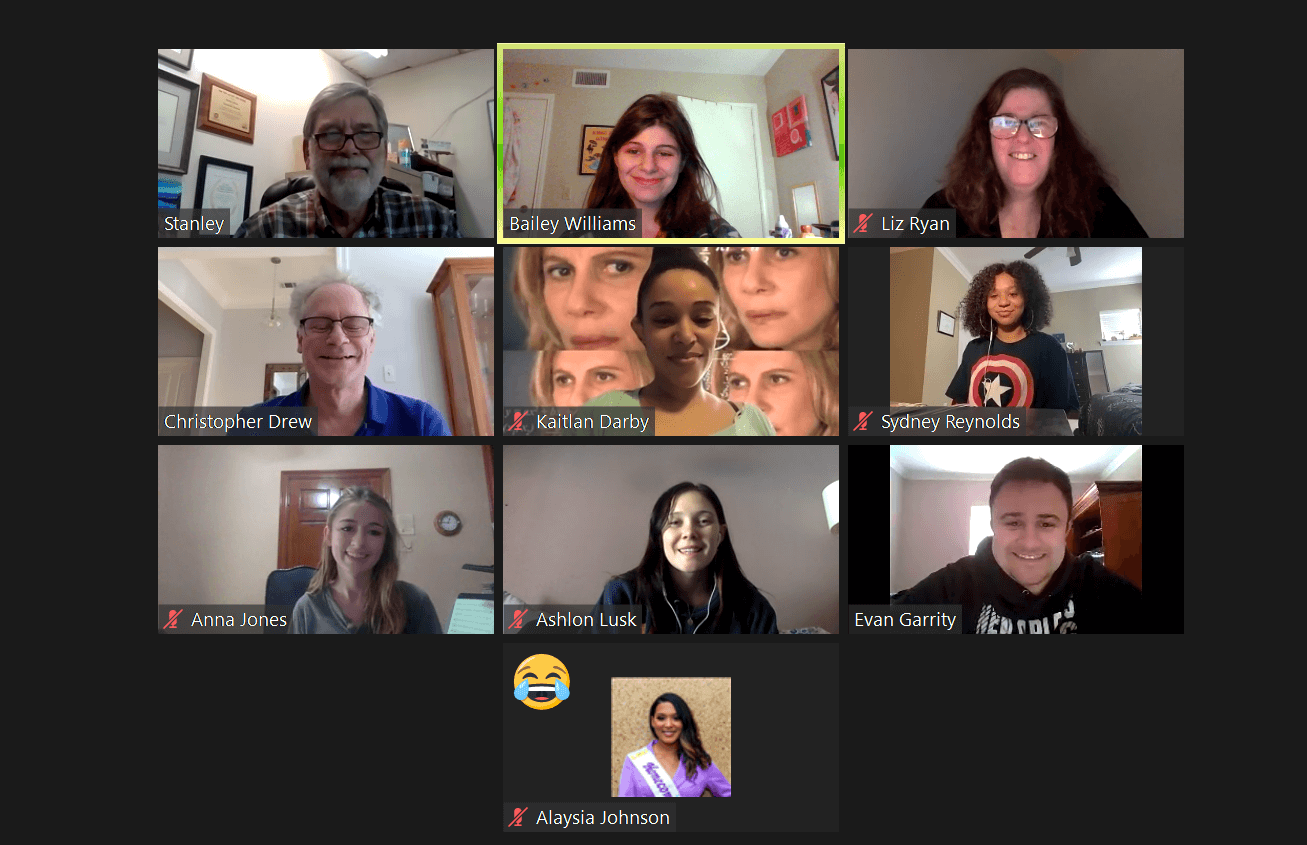

Awards for Cold Case Project’s Series on the 1960 Shooting

The LSU Cold Case Project five-part series on a 1960 shooting in Monroe was cited by journalists and organizations.

The Cold Case Project reporters were named semifinalists for the 2022 Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting, an award by the Harvard Kennedy School for reporting that impacts U.S. public policy. They were the only students recognized.

Student reporter Rachel Mipro was cited for her work in the series, placing third nationally in explanatory reporting in the 2021-2022 Hearst Journalism Awards, for the first story in the Fuller series.

The Marshall Project, the nation’s top criminal-justice news site, praised the series in September 2021 as “a cold case narrative that radiates injustice, outrage and impunity.”

Jerry Mitchell, the director of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, described the LSU Cold Case Project reporting team as “a shining example of what journalism should be.”

Robert Fuller FBI File

The LSU Cold Case Project obtained the FBI’s Robert Fuller file (3,431 pages) through the Freedom of Information Action.

The file chronicles the rise of the Original Knights in Louisiana as well as other Klan groups. It also follows Fuller’s years in the Klan and the violent acts of Klansmen statewide.

Additionally, the file discusses the work of informants.