Jack Seale was a well-known Klansman in Natchez, Miss., who was a suspect in two murder cases, an alleged arsonist and later, an FBI informant.

Seale had a fearsome reputation and once got into a fist fight with FBI Agent Billy Bob Williams at the scene of a fire in Natchez during the 1960s.

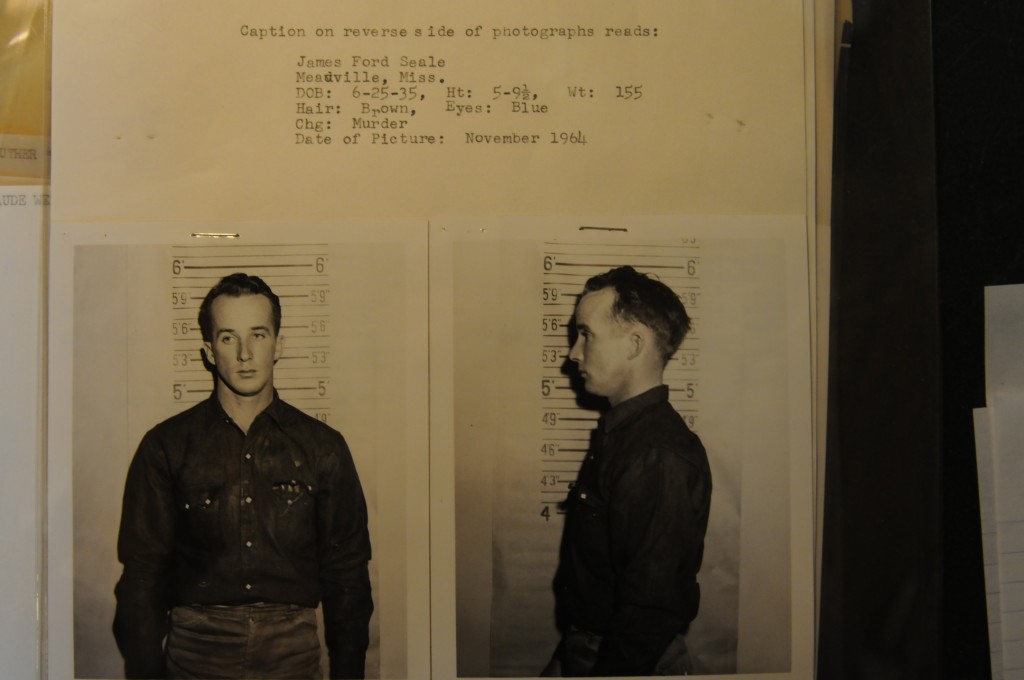

Seale, along with his father, Clyde, were suspects in the 1964 murder of two Black teens in Franklin Miss., and the 1965 murder of former Klansman in the same county. Seale’s brother, James Ford Seale, was convicted in the murder of the teens in 2007 and died in federal prison.

The Concordia Sentinel covered the Klan life of Jack Seale for several years. Before his death in 2007, James Ford Seale was told that the Concordia Sentinel had reported that his late brother, Jack Seale, had been an FBI informant. James Ford Seale was reportedly stunned by the news.

The following are excerpts from three stories on Jack Seale published by the Sentinel. The LSU Cold Case Project provided FBI documents to the Sentinel’s former editor, Stanley Nelson, who is now an adjunct professor at LSU working with the cold case project.

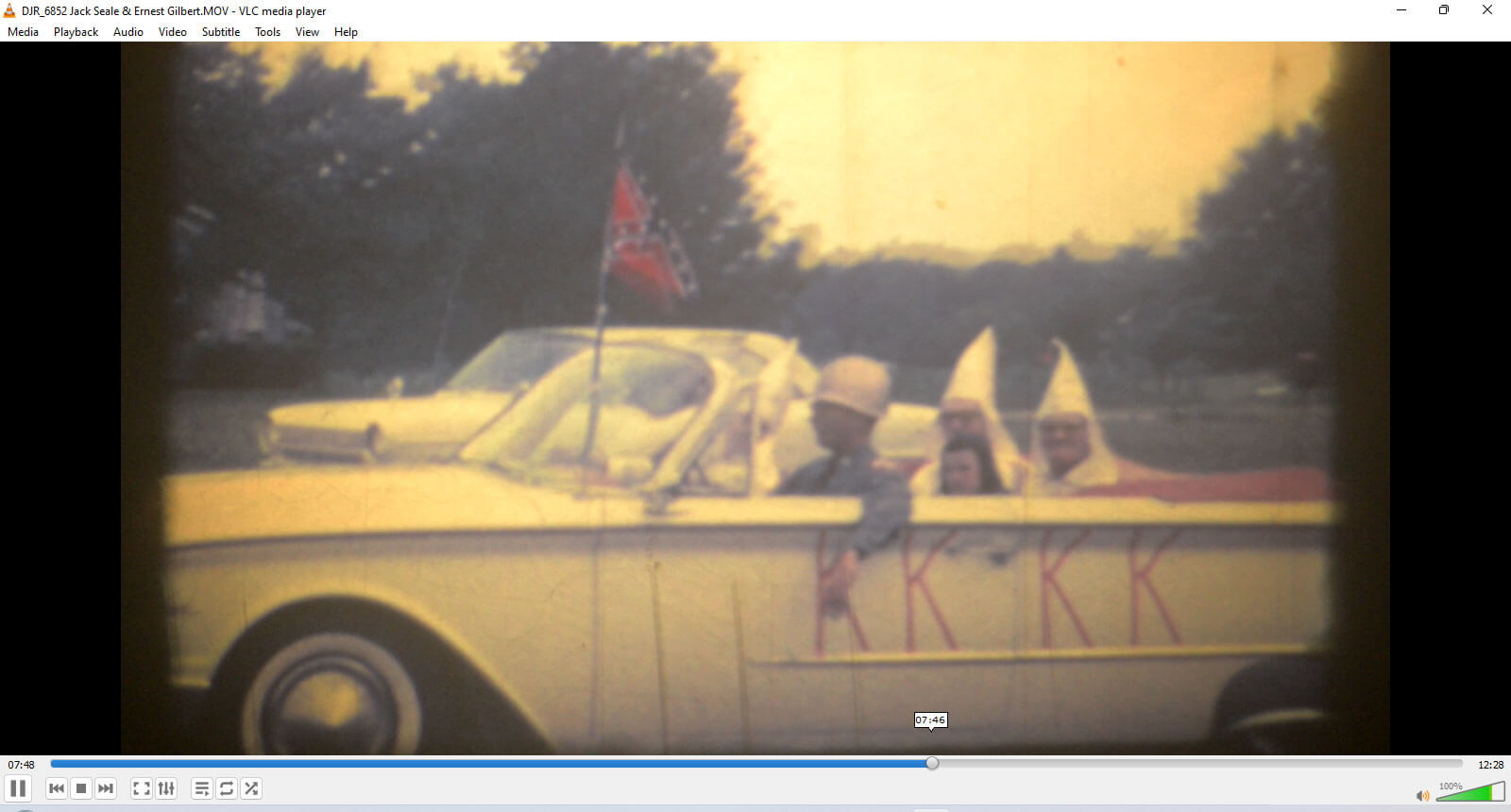

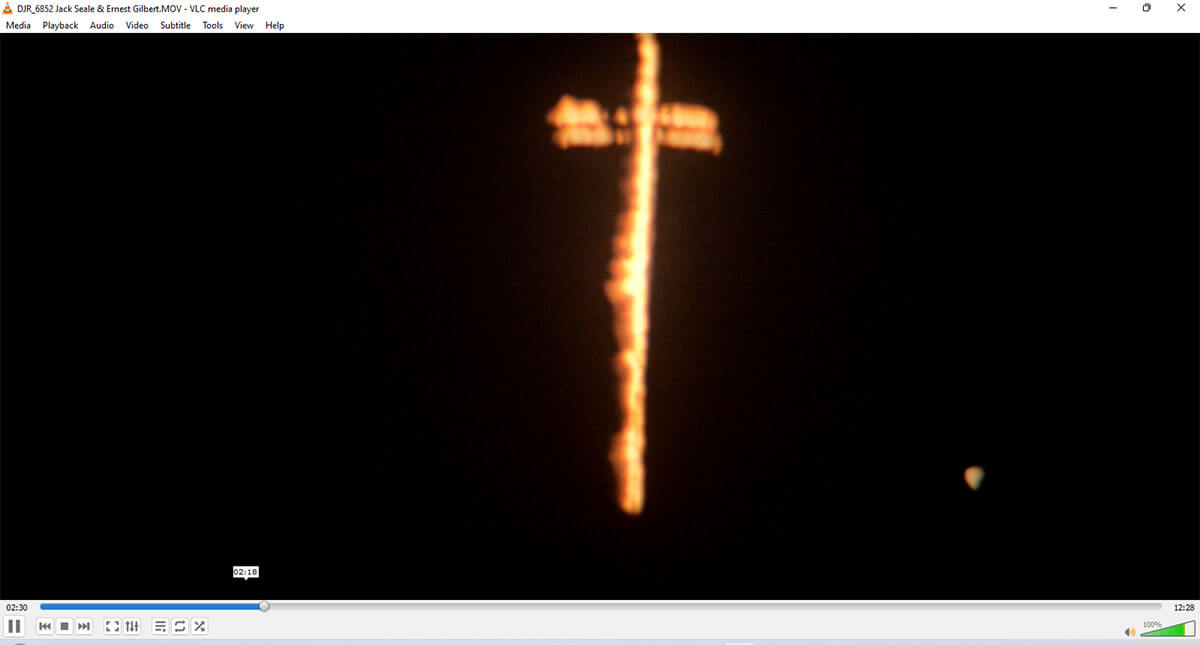

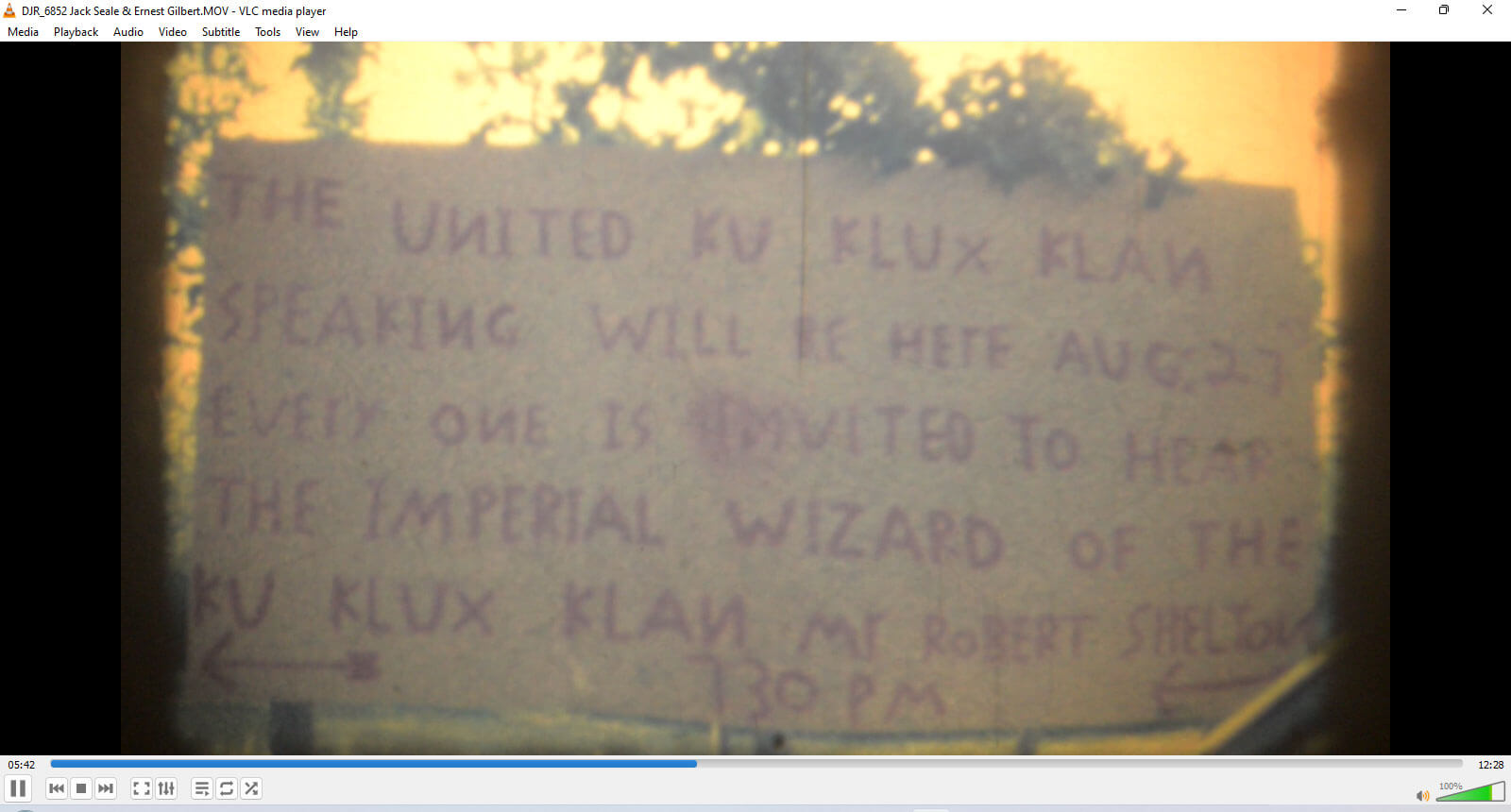

Additionally, in addition to FBI documents on Seale, are photos taken from film footage of Klansmen preparing for a Klan rally. The video was shot by Seale’s friend, Ernest Gilbert, who also was an FBI informant who secretly reported to the FBI in 1964 that Jack Seale was involved in the murder of the two Black teenagers.

FBI file reveals Seale became paid informant

(Concordia Sentinel, Nov. 12, 2009)

Myron Wayne “Jack” Seale of Natchez was a notorious Klansman implicated along with his brother and father for the Franklin County, Miss., murders of two Black teenagers in 1964 and the 1965 murder of a fellow Klansman for allegedly informing to the FBI.

Seale, who was 40 in the winter of 1967, had been a member of a savage White Knights klavern in Franklin County, Miss., led by his father, Clyde Seale. The Seales were suspects in the May 1964 murder of two 19-year-old Meadville, Miss., men — Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore — a crime for which Jack Seale’s brother, James Ford Seale, was convicted. James Ford Seale died in prison.

In August 1965, the Seales — Clyde, Jack and James Ford — were suspected as being part of the Bunkley-Meadville Klan group that beat Earl Hodges to death. A 47-year-old Franklin County white man, Hodges, who had two sons, operated a service station in Eddiceton.

He was a World War II vet, a Mason and past commander of the American Legion post in Meadville. He was also a Klansman who wanted out of the Klan. Authorities believe Hodges was murdered because he may have committed what was considered an unforgivable sin — informing to law enforcement.

How, then, could Jack Seale just two years later commit the ultimate sin against the Klan and betray his KKK brotherhood?

The answer was money.

“From experience, I can understand what developed,” said Billy Bob Williams when told of Seale’s informant status. Williams was assigned to Natchez during the era. From July 26, 1964, to April 4, 1966, he was a resident agent in the city charged with assisting, advising and furnishing intelligence to state and local law enforcement authorities as well as ensuring the safety of Civil Rights groups. Williams and Seale never liked each other, he said, and once the two got into a fist fight with Williams delivering the first blow.

“I knew Jack Seale from the time of my arrival,” said Williams. “He was openly a member of the United Klans of America … My encounters with these individuals usually took the form of good-natured bantering, but Seale was prone to insults and barbed criticism. I figured him to be a bully and a braggart who was all mouth and a coward. I could see that he could be capable of violence, but he would need to be part of a group.”

“Once he (Seale) made the decision to betray his father, brother and Klan associates he became a Judas-like character with not a friend in the world,” Williams said of Seale’s decision to inform. “His FBI contact would have had total control of him from this point on. His behavior was typical of all informants I have known who were initially motivated to inform for money.”

Before he became an informant, Seale’s garbage disposal business was failing, and he was worried the Jackson bombing was creating bad publicity for Klansmen who were facing trials. His own trial for the bombing of a Natchez jewelry store was upcoming as was the trial of three Klansmen accused of the brutal 1966 murder of a 67-year-old Black man, Ben Chester White, a resident of Adams County.

Jack Seale had switched from the White Knights to the United Klans of America in 1965. He had been subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1966 during its probe of the Klan and he had been arrested, but never convicted, for a 1963 attack on two Civil Rights workers near Fayette, Miss.

Records show that at 10:30 p.m. on March 7, 1967, eight days after the Jackson bombing, FBI agent Benjamin F. Graves got a phone call from Seale, who asked Graves to meet him in the middle of the night. Two days before the phone call, Graves had quizzed Seale about the bombing.

Just months earlier, the FBI considered bringing Seale in as a confidential racial source, even as Seale was active almost daily in Klan projects, including the bombing of the Ritz Jewelry Store. Because of his background and because of his possible prosecution in that jewelry store bombing, Seale was turned away as an informant although agents were authorized “to accept any information he volunteered.”

But the urgency in solving Wharlest Jackson’s murder had changed the FBI’s strategy, and when in the middle of the night of March 7, 1967, Seale wanted to meet Graves, the agent agreed.

Seale told Graves that he was $6,000 in debt and had no life insurance. He said for that amount he would furnish the bureau the names of SDG members and information about each man. He needed to get out of debt to insure at least a degree of financial security for his family, he said, because there was a good chance he would be killed for ratting on the SDG.

Graves told Seale that the bureau paid for information on a “cash on delivery” basis. He said Seale would first have to provide information so he could determine whether Seale knew what he was talking about.

After thinking it over, Seale identified a few men he said were SDG Klansmen, including two Concordia Parish men — Red Glover, an Armstrong Tire employee, and the man the FBI determined was the head of the SDG, and Kenneth Norman Head, also a suspect in murders and beatings.

Seale said the first he heard of the SDG was in late summer or early fall 1965 when Klansman Ernest Finley of Natchez asked Seale and Klansman L.C. Murray “to join a secret group.” At that time, Seale said he and Murray were traveling throughout Mississippi promoting the UKA, so he didn’t act on Finley’s invitation.

A short time later, Finley died and at his funeral, Seale said a silver dollar placed on a chain in the center of a wreath caught everyone’s attention. The FBI learned that each SDG Klansman was given a silver dollar by Glover as a means of identification in the group. Seale said he assumed that the wreath with the silver dollar was sent by the secret Klan group, although there was no card on the arrangement. Seale said he believed the SDG was likely responsible for Jackson’s murder because “all members are the type individuals who could commit such a crime.”

In considering Seale as an informant, the FBI and the Justice Department pondered these facts:

— Probes in Natchez for the previous three years had repeatedly implicated “a small group of individuals” responsible for the murders and acts of violence.

— These individuals were “fanatical diehards,” dedicated to segregation, and “extremely callous about using murder as a tool in fulfilling their plans.”

— These men were hard to reason with, secretive, klannish and trusted “only associates who have proved themselves in acts of violence comparable to their own.”

Just as importantly, the bureau considered Seale’s violent background, particularly two unsolved murder cases in which he had been implicated.

Along with his father and brother, Seale had been identified by Ernest Gilbert, a White Knights leader and FBI informant known as JN-30 from Brookhaven, Miss., as having been involved in the Dee-Moore murders. According to a Sept. 18, 1964, FBI document, Gilbert said Jack Seale and Klansman Ernest Parker told him about putting two Black men “in the river” while they were still alive by anchoring them to a Jeep motor block. Gilbert reportedly lived in constant fear for his life.

Seale had sources deep within the Klan and was close to many suspected SDG members, records show, and had “been so deeply involved in violence that his defection (from the Klan) would be quite incomprehensible to his Klan associates.”

But Seale had to be “recognized for what he is,” said one FBI memo. “He is no Rhodes scholar, he is a leader among the ‘Kluckers’…”

Seale was warned by the bureau that no assistance would have offered him in any of his legal entanglements, that if he infiltrated the SDG he would be acting on his own and not as an FBI employee and that the bureau “would not condone any acts of violence or lawlessness on his part.”

But how much should Seale be paid?

The FBI considered but rejected the payment of a one-year premium for a $6,000 life insurance policy on Seale’s life naming his wife and children as beneficiaries. On March 16, 1967 — with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s blessings — authority was granted to pay Seale $500 to join the SDG, and to identify SDG members and suspects in Klan crimes. If Seale provided information that resulted in “successful prosecution,” consideration would be given to paying him “a substantial amount.”

Once his alibi on the night of the Jackson bombing checked out, the deal was offered. Seale accepted. At that point he was assigned an informant number within the FBI’s Jackson, Miss., office — JN-229.

Did Jack Seale thwart plan to bomb MIBURN jurors?

(Concordia Sentinel: Nov 19, 2009)

Informants in 1967 and was credited in preventing violence against federal jurors who convicted seven Klansmen for the 1964 murders of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Miss.

FBI documents show that Myron Wayne “Jack” Seale talked the head of a Klan offshoot, the Silver Dollar Group (SDG) — Raleigh Jackson “Red” Glover — out of putting dynamite under the houses of the 12 jurors who had convicted seven Klansmen in the FBI case known as MIBURN (Mississippi Burning.) The Klansmen were among a dozen accused in the murders of civil rights workers Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, both white, Jewish and from New York, and James Chaney, a Black Mississippian.

The three men — whose ages were 20 to 24 — were shot to death on June 21, 1964, the first day of Freedom Summer. Their bodies were dumped into an earthen dam. On October 20, 1967, the federal jury in Meridian, Miss., charged with determining whether the civil rights of the victims had been violated, reached its verdict.

A day later, Jack Seale, 40, was riding to Kentwood, La., with three other Klansmen, including SDG head Red Glover of Vidalia, James Horace “Sonny” Taylor of Harrisonburg, La., and an informant known as NO-1325, a Ferriday mechanic, FBI records indicate agents learned. During the car ride, Glover, furious with the jury’s verdict, said “someone should go up to Meridian and help out by putting dynamite under the houses of Jury members.” Glover said it wouldn’t help the Klansmen just convicted, but it “would make the next jury think.”

Seale, according to FBI documents, quickly made another suggestion. He said it would be “better to have someone telephone jury members throughout the night and also have ambulances and fire trucks sent to their houses.” Seale volunteered instead to consult other trusted Klansmen before action was taken. Apparently, Glover soon gave up on the idea of the bombings.

While none of the MIBURN jurors were harmed or their homes bombed, some were threatened. Reporter Jerry Mitchell reported in The Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, Miss.) in 2000 that for six weeks after the verdicts, U.S. marshals guarded the homes of the jurors.

On whether the protection was provided because of Glover’s threat, Mitchell said, “That matches up with what jurors told me, and certainly makes sense.”

In the meantime, the FBI was elated with Seale’s quick move to avert violence, an affirmation of its decision in March 1967 to make Seale a paid informant in the aftermath of the car bombing murder of Wharlest Jackson, a 36-year-old married father of five who died just blocks from the Armstrong Tire plant in Natchez. An employee of the plant, Jackson was targeted by Klansman because he had taken a position formerly held by white men only.

In a massive investigation following the murder, the FBI determined that a secret Klan cell known as the SDG was likely responsible for Jackson’s murder as well as that of Ferriday shoe shop owner Frank Morris and Vidalia Shamrock Motel porter Joseph “Joe-Ed” Edwards. SDG members were also believed responsible for other crimes, including arsons, bombings, beatings and thievery.

Because the FBI lacked jurisdiction in many of these cases, and because the FBI believed the Klan had a safe haven among law enforcement authorities in Concordia Parish, the bureau broadened the scope of the Wharlest Jackson probe — known as WHARBOM — to neutralize violent Klansmen, to infiltrate the SDG and to identify Wharlest Jackson’s killers.

Jack Seale soon emerged as one of the FBI top informants who, along with other informants, worked to neutralize Glover and other violent Klansmen in what the FBI called “a race against violence.”

Glover was considered one of the lead suspects in the bombing of Jackson in 1967 and the 1965 bombing of George Metcalfe, a NAACP official and Armstrong employee like Glover and Jackson, who survived the attempt on his life. FBI files paint the 45-year-old Glover in 1967 as the undisputed head of the SDG, who hand-picked SDG members and gave his followers silver dollars as a means of identification and unity.

Under indictment for the 1966 bombing of a Natchez jewelry store, Jack Seale probably wouldn’t be convicted, the FBI surmised while pondering whether to bring him on as an informant. While noting that public tolerance of the Klan was diminishing, the bureau concluded that “there is not the remotest possibility that he will be convicted because juries in this county are not inclined to convict in cases which appear to be racially connected.”

This assessment is one reason the conviction of the seven Klansmen in the Philadelphia, Miss., murders came as a shock. The trial in Meridian revealed that White Knights’ klaverns in Neshoba and Lauderdale counties conspired to kill Schwerner, who was given the nicknamed “Goatee.” Unable to locate the busy activist, the Klan decided to lure him to Neshoba County by burning the Mt. Zion Church.

That plan worked, and Schwerner, accompanied by Goodman and Chaney, came to investigate the church burning after which the men were arrested by a Neshoba County deputy on a speeding charge, jailed and later released at night when overtaken by Klansmen and shot to death, their bodies buried in an earthen dam.

In summing up the government’s case, federal prosecutor John Doar, the Assistant Attorney General heading up the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department, said: “The sole responsibility of the determination of guilt or innocence of these men remain in the hands it should remain, the hands of twelve citizens of Mississippi.”

Some of the 12 defense attorneys argued that the “outsiders” were stirring up the locals and said the government had used paid informants to lie against good Mississippi citizens. Said one defense attorney: “Mississippians rightfully resent some hairy beatniks from another state visiting our state with hate,” adding that the “so-called (civil rights) workers are not workers at all, but low-class riff-raft…misfits in our own land.”

Earlier in the trial, defense attorney Laurel Weir asked a black minister this question concerning the civil rights workers: “Now, let me ask you if you and Mr. Schwerner didn’t advocate and try to get young male Negroes to sign statements agreeing to rape a white woman once a week during the hot summer of 1964?” This lie and others like it were often spread by the Klan to frighten the white populace, but Judge Harold Cox reacted quickly to the question and lambasted the defense attorney. He warned the others that such baseless questions would be harshly rejected.

Cox sided with the Jury’s decision, too, adding, “It would be unthinkable for a jury to bring in any other verdict on the defendants.”

Florence Mars, whose family was among the pioneers of Neshoba County, sat through the trial and wrote a book in 1977 called, “Witness in Philadelphia.” She said the “convictions were a turning point in Mississippi. This was the first time a jury in the state had returned a guilty verdict in a major civil rights case since Reconstruction, and the convictions marked the end of a long chain of widely publicized and unpunished racial killings that began after the Supreme Court decision of 1954,” known as Brown vs. Board of Education. In that case, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional, and that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

The day after the Jury’s verdict, Seale thwarted Glover’s attempt to use dynamite to send another message to potential jurors in Klan trials. By this time in October 1967, informants were reporting to the FBI that Glover was drinking heavily, was paranoid and feared that he would be arrested and convicted in the Jackson murder, which didn’t happen. He was never charged.

“I’ve lived a full life,” he told his closest associates.

Seale, on the other hand, was undergoing a personal transformation, according to documents, as he once persuaded Glover to provide him with explosives, which Seale quickly placed into the hands of the FBI. The FBI also said that Seale, who died in 1974, had gained the complete confidence of Glover who was beginning to confide in Seale.

Seale was “no longer prone to commit acts of violence…. has expressed his opinion that acts of violence are not the answer to the problems of the South,” the FBI concluded in 1967.

Mayor refuses to reduce Seale’s bond in Ferriday case

(Concordia Sentinel: Jan 11, 2012)

When the head of the United Klans of America in Mississippi needed help getting a fellow Klansmen and murder suspect out of jail in Louisiana in 1966, he turned to Deputy Frank DeLaughter of the Concordia Parish Sheriff’s Office, a notorious cop known for his brutality and also a card-carrying KKK member.

But DeLaughter’s influence carried little weight with Mayor Woodie Davis of Ferriday, who in 1962 had fired the patrolman from the town police force for misconduct. Davis told DeLaughter that the bond for Natchez Klansman Myron Wayne “Jack” Seale on a charge of driving under the influence was $250, a hefty sum in 1966.

The deputy asked the mayor to release the 37-year-old Seale without bond.

The mayor said no.

Klansmen interrupted the mayor’s sleep three times that night, but he refused to give them what they wanted, and they finally paid the bond.

Seale was arrested by Ferriday police during the early morning hours of Feb. 14 on the DWI charge. Davis told the FBI in 1967 that Seale’s car was searched because arresting officers had a tip that the trunk of his 1965 Chevelle Super Sport was filled with stolen typewriters.

But inside officers found something quite different and lethal: A cache of weapons and ammunition, including a .38 snub nose pistol, a Colt AR-15 .223 caliber modified automatic rifle, a .30 caliber carbine rifle and more than 635 rounds of various types of ammunition. Additionally, police found two bayonets, two traffic blinker lights and two walkie-talkie radios.

Following the arrest, Seale was booked in the Ferriday jail. A short time later, Davis received a visit from James Scarborough, who was head of the Ferriday-Clayton unit of the Original Knights. When told the amount of the Seale’s bond, Scarborough told Davis he didn’t have “that kind of money” and left, according to FBI records.

Later, Mississippi United Klans of America (UKA) leader E.L. McDaniel and DeLaughter knocked on Davis’ door. DeLaughter did most of the talking, but his attempts to persuade Davis to allow Seale to walk out of jail without bond failed.

Thirty minutes later, McDaniel returned with the $250, paid the bond and Seale was released.

Seale had an arrest record dating back to the 1940s beginning when he was in the Navy. He was also arrested along with other Klansmen for the 1963 beating of two Civil Rights workers in Port Gibson, Miss., and authorities later confiscated an arsenal of weapons from his home. Additionally, he was a suspect in the 1964 murder of two Meadville, Miss., African-American teens and the 1965 murder of a former Klansman.

Mayor Davis told the bureau in 1967 that the materials confiscated during Seale’s arrest were in storage at the police department but would likely have to be returned to Seale because no fully automatic weapon was discovered and the other items on their own were not illegal to carry.

Later in 1966, Seale was indicted by an Adams County Grand Jury in Natchez — but never convicted — for “willfully and unlawfully placing a bomb at or near” Oberlin Jewelers in downtown Natchez “to harm or destroy the contents therein.”