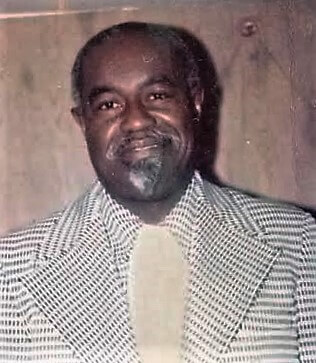

Tommie Lee Jones (1936-2007) was a Klansman from Natchez, Miss., who became one of the earliest and most violent members of the secret Klan cell known as the Silver Dollar Group, which has been linked to eight murders in southeastern Mississippi and northeastern Louisiana from 1964 to 1967.

When Jones attempted to kidnap a Black man from his home in 1964, the man in defending himself shot Jones in the face as Jones fled the scene.

An employee of International Paper Company, Jones became a member of the Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in late 1962 and in 1964 became a member of the deadly Klan offshoot known as the Silver Dollar Group.

During its multi-year investigation into the Silver Dollar Group, the FBI learned that Jones had been involved in multiple wrecking crew projects involving intimidation, beatings and arson. Additionally, Jones was a suspect in the 1964 arson murder of Ferriday shoe shop owner Frank Morris and in the 1967 car bombing murder of Wharlest Jackson in Natchez.

As the FBI using informants began work to neutralize the Klan and solve Klan crimes, agents made several visits to Jones’ home to confront him with several acts of violence in which Jones was believed to have participated.

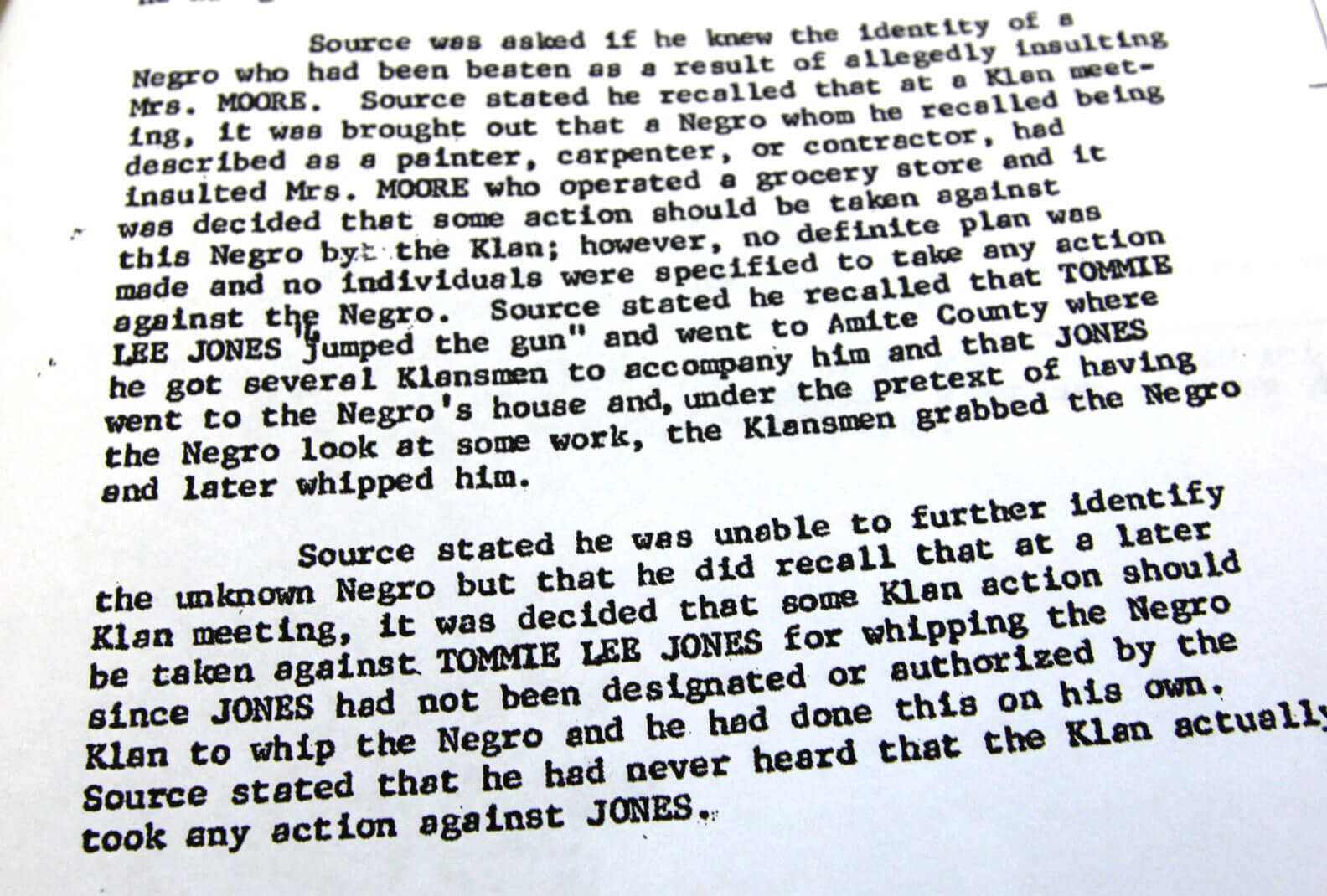

When asked if he had beaten an African-American man in Natchez in the early 1960s for allegedly insulting a white woman, Jones quickly admitted that he had but was puzzled by the question, remarking, “This was just a beating, nothing serious.”

The FBI learned from an informant in 1967 that three years earlier in February 1964 Jones had participated with three other Klansmen in the attempted arson of an African-American Masonic Lodge in West Feliciana Parish, La., not far from Woodville, Miss., where on that same night Clifton Walker, an African-American returning home from work at a Natchez mill, was ambushed and shot to death on Poorhouse Road.

In his book, “Devils Walking: Klan Murders along the Mississippi in the 1960s,” Stanley Nelson reported that Jones may have been involved in the murder of Walker. Although Jones was not a suspect at the time, Nelson pointed out that Jones was a close friend of Douglas Byrd, a Klan leader who clearly had a motive for the Walker attack.

The Mississippi Highway Safety Patrol had learned from Byrd’s sister-in-law that a few weeks before the shooting she had told Byrd that Walker had made a pass at her in late 1963 where she worked as a waitress at Nettles Truck Stop near Woodville. There was no greater sin in the Klan world than a Black man attempting to have any type of relationship with a white woman.

Nelson reported that this could have been the motive in the murderous shooting attack of Walker in early 1964.

Jones Joins Silver Dollar Group in Spring 1964

In the spring of 1964, Jones became one of the first members brought into the Silver Dollar Group. Members carried a silver dollar minted in the years of their births. Red Glover, the leader of this violent Klan cell, handpicked each member and presented each a silver dollar as a symbol of unity.

In 1967, the FBI tracked down a former waitress of the Shamrock Motel coffee shop in Vidalia where the Silver Dollar Group was organized in 1964. The waitress said Jones and other Klansmen, including Glover, occasionally fiddled with their silver dollars in public without explaining their significance.

Later in 1964, Klansmen tossed an explosive into the yard of Natchez Mayor John Nosser. The explosion damaged neighboring homes. When confronted about this act of violence, Jones denied involvement but did admit to making several anonymous telephone calls to Nosser attempting to bully the mayor into firing the Black employees who worked in his grocery stores.

As reported in “Devils Walking,” Jones was en route to a Silver Dollar Group fish fry in the summer of 1965 when “he was arrested by Ferriday police for pistol-whipping a black man with a .25 caliber revolver. Jones claimed that the man had cut him off on the highway. At the scene of the accident, the officers observed blood pouring from a cut to the victim’s head, the imprint of the pistol butt clearly visible. Inside Jones’s car was a massive German shepherd. The officers instantly tagged Jones a ‘smart mouth’ and took him to the Ferriday jail, where he was booked for assault with a gun and disturbing the peace.”

Jones called his wife, and she called another Klansmen to put up the $500 bond. The charges were later reduced to disturbing the peace. Jones paid a $50 of a $150 fine, the remaining balance was waived.

Jones shot in the face by Black man Jones had tried to kidnap

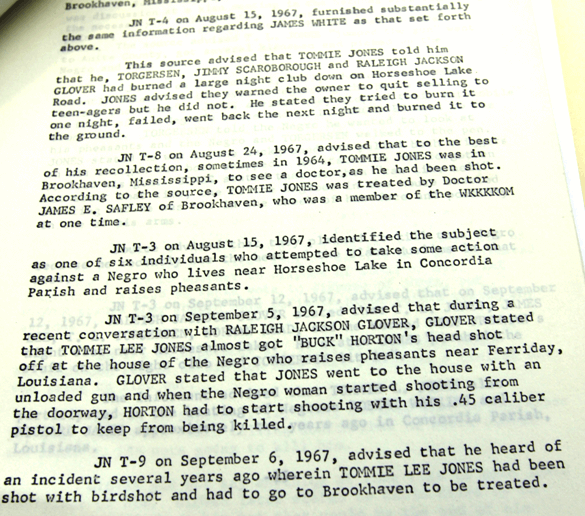

In Concordia Parish in 1964, as sometimes happened, Jones and his comrades attacked the wrong man. When Jones opened fire on African-American James White Sr. in his front yard of his home in Concordia Parish, White fired back and later told his family that he was certain he had wounded one of his attackers.

On May 25, 2010, the Concordia Sentinel published an article on this incident and interviewed the children of White 46 years after the attack. The article follows:

Frank Morris and James White Sr. were best friends, so close that some folks believed the two were related though they were not. When Morris at the age of 51 was fatally injured during the arson of his shoe shop in Ferriday by Klansmen in December 1964, White, 45, went to see him at the hospital.

White, now dead, had experienced confrontations with Klansmen during the months preceding Morris’ murder, his children recall. Once, when a Klansman opened fire on White in his own front yard, his children say White fired back and felt certain that he wounded one of his attackers.

White’s belief was true. FBI records obtained by the Sentinel and the Syracuse University College of Law Cold Case Justice Initiative reveal that during that confrontation 46 years ago, Klansman Tommie Lee Jones of Natchez was hit in the face by a blast from White’s shotgun. Jones, who worked at International Paper Company and died a few years ago, was treated clandestinely by a doctor in Brookhaven, Miss., hours after the shooting and recovered, records show. By early 1965, Jones and others would be considered suspects in the arson of Frank Morris’ shoe shop.

Three of White’s children — James Jr. of Chicago, Trevor of Baton Rouge and a daughter who asked not to be identified — were astounded that the man their father shot was named in FBI records. They never knew who any of the men were in their front yard on that February night long ago.

“Daddy knew he hit one of them,” said White’s daughter, who was 12 at the time. “He was sure of it.”

White raised and sold pheasants at his home. He also sold clothing door-to-door. When in Ferriday he almost always visited Morris at the shoe shop and when he learned that Morris was in the hospital following the arson, he went to see him. White told the FBI he initially waited outside Morris’ room as visitors, hospital workers and others came and went.

Once Morris was alone, White went in and pleaded with his old friend to tell him what happened, but Morris refused. White told the FBI that Morris said he didn’t want to get White “mixed up in the affair.”

“Daddy believed Frank knew who did him in, but Frank didn’t want Daddy to get involved,” said son James Jr., then 18. “He probably knew Daddy would go after the people who did it.”

Son Trevor, who was 8, recalls his father quoting Morris saying of the arson, “I just can’t believe it!” Trevor said his dad believed Morris knew his attackers either by face or by voice.

Eleven months prior to the arson in 1964, as Klan violence escalated throughout the region, the James White family lived on the Stacey-Monterey road (Hwy. 129), just south of its intersection with U.S. 84. White told the FBI that on at least 17 occasions passing motorists along the road had fired gunshots onto his property. Unbeknownst to White was the fact that Klansmen in Concordia and Natchez had targeted him because they believed he was a Black Muslim and was stockpiling weapons as a part of a black uprising, according to FBI records. Adding to the Klan’s suspicions, records show, was the fact that White had a goatee.

“Daddy didn’t know what a Black Muslim was then,” said James Jr. when told of the reason for the Klan attacks. He chuckled and said, “Unbelievable!”

But White was a man, his children say, who would fight back when threatened by anyone, and would do anything to protect his family. FBI records show that Klansmen intended to force White at gun point into a vehicle and transport him to a secluded location to whip him. In similar cases at the time, Klansmen stripped their captives, whipped and beat them, sometimes forced them to drink a laxative and quizzed them endlessly about the NAACP and civil rights.

Along the Monterey-Stacy road in Concordia in February of 1964, the White family was inside their home on a chilly Saturday night. Only James Jr. was away. He was at a basketball game in Ferriday. Around 8 p.m. as a hard rain fell, White told the bureau he heard a male voice shouting that he wanted to buy some pheasants.

“It was the weekend and daddy told the man to come back in the morning because of the weather,” Trevor told the Sentinel. “It was dark and it was raining. You couldn’t see anything. The man said he was from out of town and couldn’t come back.”

It was not unusual, said White’s children, for customers to visit their home at all hours to buy birds kept penned on their property.

White told the FBI that he observed outside his front door a man wearing dark clothes with the bill of a cap pulled low on his forehead and a jacket pulled up around his neck.

White’s property was fenced with one gate at a side entrance and another in the front yard. A ditch separated the front yard from the highway. He said a red pickup was parked near the gate at the side entrance also observed a car parked on the highway with its headlights turned off but the brake lights on.

The man White confronted outside his front door nervous and chain-smoked cigarettes. Immediately suspicious, White asked the man where he was from. He said the man answered Crossett, Ark., before turning to White and saying, “We’ve come for you. You’re the mean one. Get in the truck.” White said the man poked a pistol in his stomach while at that moment White observed another man holding a shotgun rising from a crouched position at the corner of the house near the red pickup at the side gate.

(Note: The man with the shotgun was apparently Jones, although some sources identified him as the man with the pistol. One informant said Jones was holding a double-barrel shotgun and that when Jones fired he heard two clicks. He had forgotten to load the shotgun.)

Preferring to take a stand rather than get into the pickup, White yelled for help from his father, mother, wife and sister inside the house while folding his umbrella and pointing it like a weapon at the man with the pistol. Attempting to frighten him, White shouted, “Now I’ve got you where I want you,” and then yelled for his father to come out of the house shooting.

“I remember Daddy running in the house,” recalled White’s daughter. She told the Sentinel that her father took the gun from the hands of her grandfather, Richmond White, who was so nervous he “couldn’t get the shells in. Daddy put the shells in the gun.”

White told the FBI that the man with the shotgun, who walked with a limp, ran to the pickup without firing while the man with the pistol ran for the front gate facing the highway and fired “wildly” several times at White and his house. White’s daughter said her father said that the man “got hooked up in the gate. That’s when Daddy fired.”

White told the FBI the man then stumbled over the gate, jumped a ditch and ran into the woods across the highway. By then the man with the shotgun was in the red truck, which stopped on the highway as the man with the pistol hopped in the back. As the truck and car sped away, White fired “several shots at the pickup,” hitting the vehicle more than once.

The event was so terrifying that White’s daughter recalled her grandmother and aunt “screaming for the police in the yard in the dark and the rain. My grandmother had a heart condition and I had to put nitro on her tongue.”

FBI documents show that Jones, in pain from the gunshot wound (bird shot), began looking for a doctor. In 1967, he admitted to the FBI that he was shot during the confrontation at White’s house but would not name any other participants.

Klansman Ernest Gilbert of Brookhaven, Miss., an FBI informant, told agents that he received a call that a Klansman had been shot and needed medical assistance. A short time later, he said Jones and others arrived at Gilbert’s office at the Houston Oil Field Material Company in Brookhaven. Jones told Gilbert that there was a pellet in the cheek of his face, that his “throat and jaw were sore and he feared infection.”

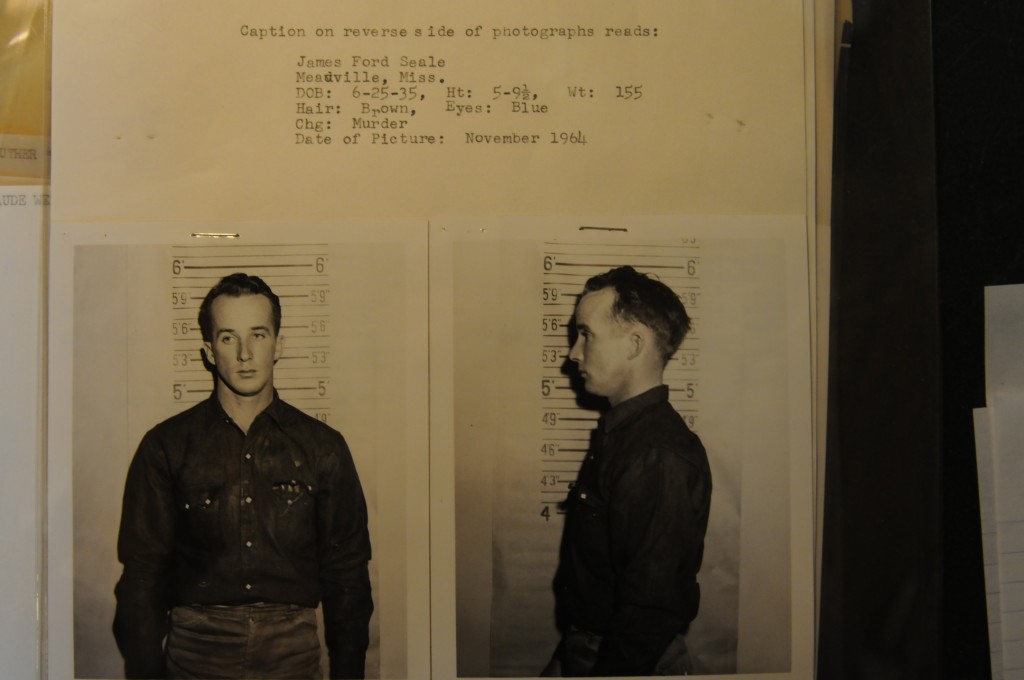

Gilbert told agents he called Dr. James Safley of Brookhaven, who agreed to treat Jones. Safley was Lincoln County Health Officer. Records show that neither Jones or Safley wanted their identity revealed to the other. Gilbert identified one of the men with Jones as Klansman Ernest Henry Avants, who was convicted in 2003 in the 1966 murder of Ben Chester White of Adams County, which was believed to be part of a failed plan designed to lure Dr. Martin Luther King to Natchez so Klansmen could assassinate him.

Safley told the FBI he treated a man who had a hole the size of a match head in his right cheek that was several hours old. He said he gave the man a tetanus shot, after which the man paid him $3 cash and left. No record was made of the visit, he said. When the FBI told the doctor that the injured man had been identified as Tommie Lee Jones, records show the doctor still refused to identify a photograph of Jones as the man he treated.

Four FBI informants told agents that Jones, Raleigh Jackson “Red” Glover of Vidalia, Thore L. Torgersen of Natchez, E.D. Morace and James L. Scarborough, both of Ferriday, and James “Red” Lee of Wildsville were involved. One informant said Scarborough was to provide protection for Jones but had forgotten to load his shotgun, while another informant said it was Jones who had failed to load the shotgun.

All were identified by informants as members of the Silver Dollar Group, a militant Klan cell formed in 1964 dedicated to stopping civil rights by violence. Each carried a silver dollar as a token of unity and secrecy and the coins carried by most were minted in the year of their births. With the exception of Lee, all were suspects in the Frank Morris murder.

Five men from the Monterey/Black River Klan, including twin brothers, had previously threatened White, said yet another informant.

White told the FBI four decades ago that he reported the shooting to the Concordia Parish Sheriff’s Office and the District Attorney’s office. He said deputies Frank DeLaughter and Bill Ogden, both suspects in the Morris murder, soon showed up at his doorstep.

White said he had taken great pains to protect a perfectly preserved footprint in the mud by his front door by placing a metal container over it. He pointed it out to DeLaughter, who White said “just snickered and continued to walk over the print.”

Two weeks after the confrontation with Klansmen in his front yard, White said a group of men drove by his house and fired shots toward his property, striking the house, a water tank, the windshield of his 1957 Ford station wagon, and the fence. White fired back with a rifle but was unsure if he hit the vehicle. He said such events had become a way of life.

In 1967, White was shown photographs of Silver Dollar Group Klansmen, including a photo of Tommy Lee Jones. Unlike many witnesses, white and black, White was more than willing to testify against his attackers in court but he was unable to identify any of the men in the photos.

Klansmen Consider Killing Jones

When the FBI confronted Jones in the fall of 1967 with his alleged crimes, the bureau noted that Jones was clearly upset that some of his Klan friends had obviously been talking and had implicated him in various wrecking crew projects. As a result, Jones for the first time admitted to agents that he was a Klansman. Though he acknowledged some of his actions, he claimed his violent acts had fallen short of murder.

“A tremendous impact on Jones has been made by this confrontation based upon info furnished recently” by informants, bureau agents noted in reports. The bureau believed Jones had been neutralized and thought there was a chance that Jones might confess to more crimes in the future.

But Jones feared at the time that some of his former Klan friends, including Glover, were out to assassinate him. In fact, a group of Silver Dollar Group members met along the Mississippi River in Natchez to discuss Jones. Some expressed their opinion that Jones was informing the FBI. Some wanted to kill Jones, but Glover decided against it.

Jones soon dashed the FBI’s hope that he would tell more when later in the fall of 1967, Jones advised that he had retained an attorney and did not plan to discuss his past Klan activities any further.