Will Haney’s legendary nightclub — Haney’s Big House — made Ferriday, LA, a destination for Black talent and music lovers

African-American businessman William “Will” Haney made Ferriday, LA, a destination for Black music lovers across the South from the 1940s through the mid-1960s as his popular nightclub — Haney’s Big House — drew emerging Black talent like Ray Charles during the Jim Crow era.

As boys, rock-n-roll legend Jerry Lee Lewis and his first cousin, soon-to-be evangelist Jimmy Swaggart, occasionally stood outside the club and reveled in the music that greatly influenced Lewis’ music career.

Due to segregation, Haney built a motel behind the club to house the Black bands and entertainers that performed in his club. But as the Ku Klux Klan reached its zenith of power during the mid-1960s during the Civil Rights Movement, Haney watched his beloved nightclub burn to the ground in 1966. While firemen claimed a faulty ice machine may have been the cause of the fire, the Black community felt Haney was targeted by Klan arsonists who detested his quiet support for Civil Rights.

He was born to Jim and Emmaline Haney of Vidalia, LA, on July 2, 1895. His grandmother briefly lived with the family. She had been born into slavery prior to the Civil War.

Years before he opened his nightclub, Haney served in Europe during World War I as a member of a world famous Black regiment. Upon his return home, he worked as an insurance agent, purchased multiple properties, opened a washateria, and operated a café and barbecue stand in the years before enlarging it to include Haney’s Big House.

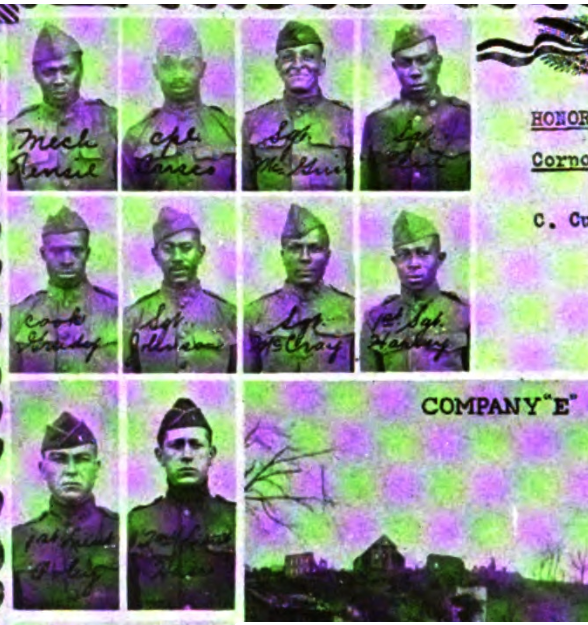

Haney’s success was anchored on his personal discipline, organizational skills and work ethic. While he may have been born with these traits, they were sharpened during his service in World War I in France where he became the highest ranking Black officer in Company E of the 805th Pioneer Infantry, a regiment of Black troops. In the history of the 805th written by white officers, it was reported that the regiment “won the reputation of being the most soldierly colored regiment in the Army of the United States.” The 805th was also known as “the greatest colored regiment in the history of America.” Some called it the “best disciplined colored organization in France.”

HANEY IN WORLD WAR I

On July 5, 1917, during World War I, the 22-year-old Haney registered for the draft in Vidalia. He was employed at the time as a teamster working for Henry Perry in Vidalia. Haney’s draft card described him as tall and slender with brown eyes and black hair. His request for an exemption to military service — because his mother and brother were dependent upon him to live — was denied.

In May 1918 after the U.S. entered the war, President Woodrow Wilson called for the organization of eight colored infantry regiments. Haney was among the first draftees to arrive in Camp Funston, Kansas, where he became part of the newly-organized 805th Pioneer Infantry, totaling more than 3,300 Black men and almost 100 white officers.

Haney checked in at Camp Funston on June 21, 1918. For six weeks, the men trained, went on tactical marches and spent time on the firing range. During this time, the white officers looked for men who showed the skills and talent needed to serve as leaders. Haney was chosen as a sergeant, one of four non-commissioned Black officers in Company E, which included approximately 200 men. Haney would rise to 1st Sergeant by the war’s end.

THE WAR IN FRANCE 1918-1919

In August 1918, Haney and his regiment traveled by train to Long Island, New York, where the 805th soldiers were clothed for war and provided ordnance. On the train ride there, the men were cheered in town after town. Along the way, the Red Cross provided coffee, candy and other goods.

On September 3, the 805th boarded trains for Quebec, Canada, where American transport vessels awaited. The regiment boarded the “Saxonia,” part of a fleet of 22 transport ships led by a British destroyer and a British cruiser. The convoy arrived in Liverpool, England, on September 16 before crossing the English Channel and landing in Le Havre, France on September 21.

Haney would soon participate in the 47-day Meuse-Argonne Offensive that involved more than 1.2 million Americans of which 26,000 were killed. The offensive was led by American General John Pershing and from the fighting emerged one of several heroes, including the best known – Alvin York — who along with seven other surviving members of his company captured 132 German soldiers on October 8, 1918.

Due to segregation, Black soldiers for the most part did not fight in battle. Instead, they were involved in various support operations crucial to the war effort.

Haney spent a year in France, primarily in the northeastern region of the country. After arriving, the 805th traveled by train to Rolanport, about 175 miles east of Paris, and later moved to Clermont-en-Argonne region of northeastern France, about 200 miles east of Paris. Here, the regiment was attached to the First Army for railhead work. They could hear the roar of the big guns along the front seven miles away and assisted as ambulances arrived with the wounded.

In addition to building roads and railheads, Company E also spent much time repairing the infrastructure destroyed by war as U.S. troops moved to and from the battlefields. Another major task was salvage operations in battle fields and along roadsides where the men collected allied and enemy weapons, cannon, clothing and blankets, rolling stock and other materials. During the year Haney was in France, more than 3,000 railcar loads of savage material was gathered by Black soldiers.

In early October 1918, Haney moved to Varennes where Company E repaired more roads and railheads. There were nightly bombardments from the Germans seeking to destroy Allied railheads, ammunition dumps and hospitals. On November 7, Company E relocated to nearby St. Juvin to repair roads. The men stayed in a large warehouse with comfortable quarters and good water. It was during this period that Company E learned that the armistice, signaling the end of the war, had been signed on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month – November 11, 1918. The men celebrated by firing rifles.

On November 14, Haney was in Briquenary where he watched soldiers returning from the front lines. Five days later, Company E moved to Verennes-en-Argonne. The men stayed in quarters once occupied by a Bavarian prince. The concrete dugouts were decorated inside and out with paint and fresco.

THE ARGONNE FOREST

Company E soon settled into the heart of the Argonne Forest, a mountainous wild 40 miles long and 10 miles wide, marked by ravines and thick underbrush. In addition to performing salvage work, members of Company E also buried the bodies of American and German soldiers found in the fields where intense battles had raged during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. At an old German bathhouse, the men for the first time in weeks enjoyed a shower. Plus, there was fresh game provided by the hunters in the company, including deer, boar, hare and partridges.

In mid-December, Company E relocated a short distance away to Charlepaux and occupied the recently abandoned quarters of the German High Command. Nearby was a graveyard where the dead of “The Lost Battalion” rested following one of the most famous struggles of the war. The Last Battalion (which was never lost) was made up of nine companies of the U.S. 77th Division, about 554 men, who had been involved in the largest American offensive of the war. During battle, the soldiers were cut off from American forces and surrounded by the Germans from October 2-7 until freed by the Americans. Less than 200 of The Lost Battalion survived.

After American forces pushed back the German army and rescued The Lost Battalion, Haney’s Company E camped out at the site. Visitors came by to see the famous location. During a period of snow and rain, the company continued to clear roads, salvage and upgrade railheads, clearing the way for victorious yet exhausted troops returning from battle. During the rare times of inactivity, the men attended classes where they received school and agriculture books. They also enjoyed playing baseball.

On May 1, 1919, Company E soldiers boarded a train for a trip through central France and the Normandy Coast. On June 17, Haney boarded the transport “Zeppelin” and headed home.

HANEY ENTERS THE BUSINESS WORLD

By 1930, according to the census, Haney was in Vidalia working as an insurance agent. It was during this period that he began to make money. Haney was 35, and married to Lillie Haney. It was noted on the census entry that his household owned a radio.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Haney could be seen walking the streets of Ferriday selling insurance for People’s Life Insurance of New Orleans. During a major flood in the 1940s, many of Haney’s policy holders were unable to work and consequently unable to pay their bills, including insurance premiums. Haney traveled to the company’s New Orleans headquarters to demand that executives not allow his customers’ policies to lapse due to the floods. The company agreed. As Haney went on to other things, he turned the insurance business over to a relative.

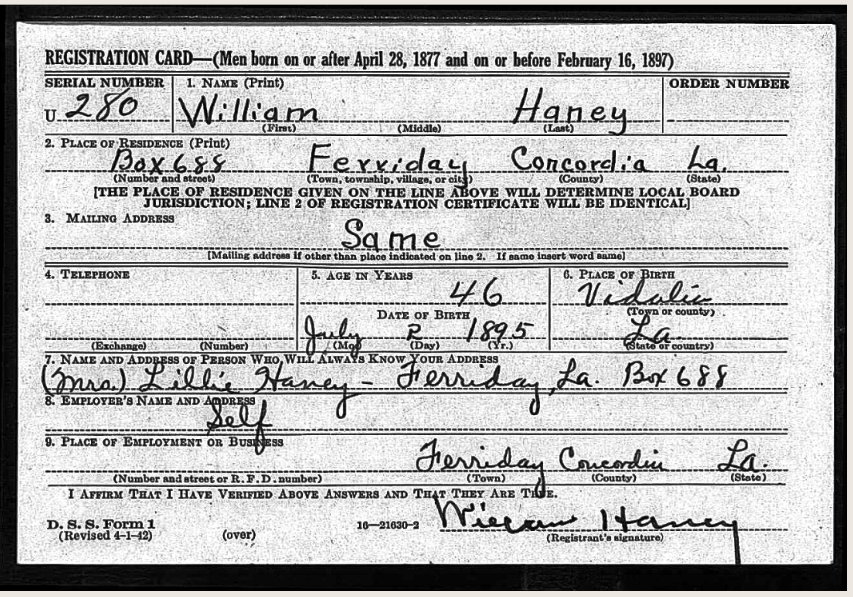

In 1942, he and wife Lillie were now living in Ferriday. They also had a daughter, Willie. Now 47 years of age, Haney was 5 feet, 10.5 inches tall and weighed 199 pounds. The 1950 census revealed that he was working 60 hours a week operating a bar and café on the 500 block of E.E. Wallace Blvd.

According to the research of Mississippi writer/researcher Scott Baretta, Haney purchased 12 properties, including the Haney’s Big House property on 4th Street between Maryland and Carolina, in March 1945. Baretta said a lot behind the lounge had been purchased in 1943 and may have been the site of Haney’s hotel.

BIRTH OF HANEY’S BIG HOUSE

During the 1940s, Haney opened what would become a popular barbecue joint in Ferriday in a building that had a dirt floor and paneled walls running halfway up the structure. A screen ran above the wall to the ceiling. In time, he added a barroom. By then, the place was known simply as Haney’s.

“It was a nice size place, and when he started making money on it, he enlarged it, and that’s when it got the name Haney’s Big House. Before that it was Haney’s Night Club,” recalled James Watkins, who as a young boy began working as a barber in his grandfather’s shop located next to Haney’s.

The operation featured “good home cooking. He always had two or three cooks on duty and he stayed open 24-hours-a-day, seven days a week. He closed twice that I remember — once when his mother died and when his brother died.”

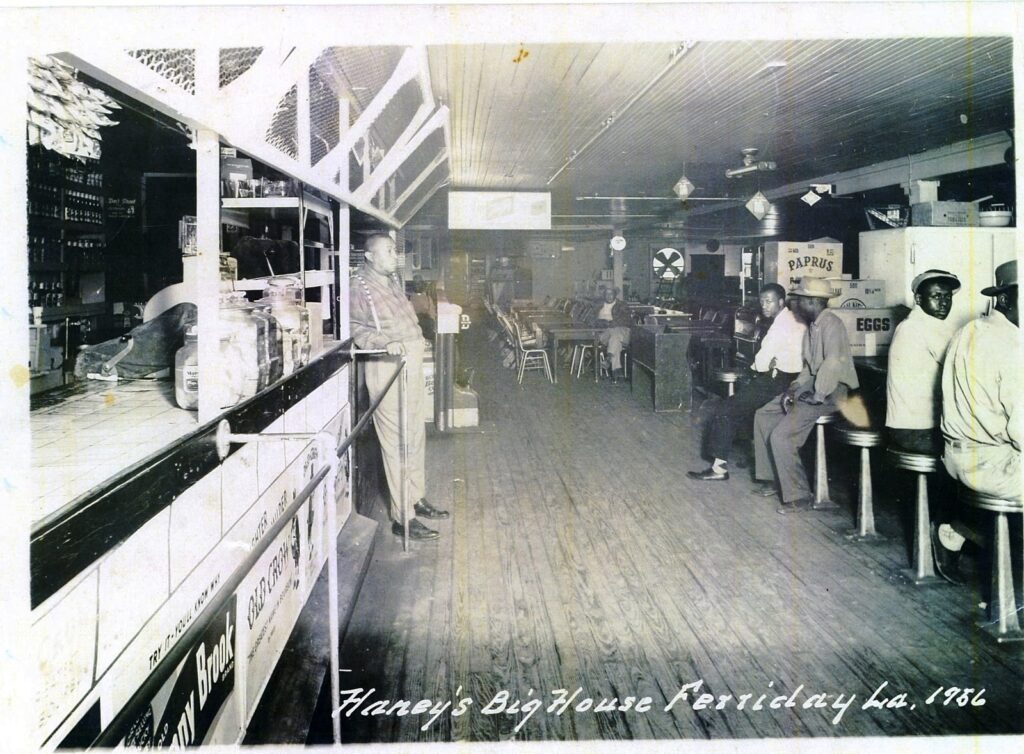

The building had two entrances. The Concordia Sentinel wrote that when “entering the door on the south side of the building there was a bar to the left. The open kitchen was in the middle of the building towards the front, surrounded by a square bar where patrons could sit on one of the 20 or so stools and dine.

“Past the kitchen was the entertainment area. When there were no dances scheduled, pool tables were located near the kitchen. The tables could be moved out of the building when entertainment was booked. About 50 {customer} tables with four chairs each were stationed in the entertainment area. The band stand was against the back wall. When musicians were performing, patrons would book a table in advance.”

All of the tables were usually reserved at least two days before the event.

The building had heat in the winter while it was cooled in the summer by two large wall fans before air conditioning was added in later years.

LIVE MUSIC & DANCING

Watkins told the Concordia Sentinel that after enlarging the business, the blues singers from the Mississippi Delta, the jazz entertainers from New Orleans and the big bands from other locales drew hundreds to Ferriday.

“The dance would start at 10 o’clock and after a while they’d take an intermission for 15 or 20 minutes and then play again until 2 in the morning,” Watkins said. “That’s when the dance was over.” But the party lasted all night, the place so full at times that “you could hardly walk by on the street.”

When the club was really hopping, Watkins estimated that 300 to 400 people would be inside and spilling out onto the streets.

POKER, SLOT MACHINES & DIAMONDS

Illegal slot machines were fixtures at Haney’s Big House as in many other bars throughout the parish.

A table in the back area of the joint was petitioned off for various games of poker. Gamblers came from Texas and as far as Memphis. Watkins recalled that the “players had money and sported diamonds and had bodyguards. They’d sit around the table with a couple of thousand dollars in front of them.”

Watkins never witnessed an argument during a game. If a player needed a bathroom break, he could safely leave his money on the table with no fear that someone would steal it. Haney would not tolerate cheating.

A game would typically begin at 10 in the morning before a break at 2 p.m. Players returned around 4 p.m. and would play into the night, but rarely all night. Spectators watched. Sometimes Haney would join a game.

HANEY’S EMPLOYEES & MOTEL

During the heyday of Haney’s Big House, Haney employed as many as 15 people on busy nights, including cooks, bartenders, waitresses, waiters and bouncers. Haney’s brother, Victor, employed fulltime at the Concordia Sentinel, worked part-time at the club. “Victor was the bouncer,” remembered Watkins. “He walked around the club with brass knuckles and he knew how to use them.”

Bertha Patterson also worked for Haney, while Mary Metcalf managed his washateria and sometimes worked at the club.

During the Jim Crow era, Black musicians were not allowed to stay in white-owned hotels. Haney remedied that problem by building the two-story Haney’s Motel, located behind the club. New Orleans jazzman Roy Brown often stayed at the motel. During the day when he wasn’t sleeping or performing, he’d go fishing.

PERSONAL LIFE

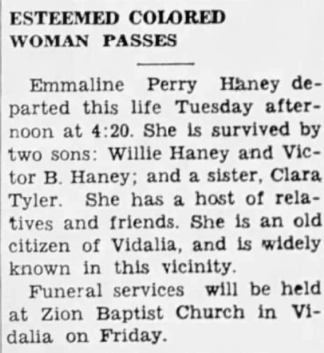

Haney began working as a child to help support his mother, Emmaline, and little brother, Victor. When Emmaline died in Vidalia in 1954, the local newspaper reported that she “was an old citizen of Vidalia and well known in this vicinity.”

By the 1930s, Haney and his wife and child lived on Fifth Street in Ferriday in a brick house. His washateria was located across the street from his home.

“He didn’t have too much time for fun,” remembered Watkins. “He was all business just about all of the time. But sometimes he would sit down and have a drink. He didn’t drink often, but when he did with some of his friends, he could tie one on.”

People who knew Haney well called him by his nickname, “House,” born through the popularity of his club — Haney’s Big House. Haney and Lillie’s daughter, Willie, went to college in North Carolina. Willie married and moved away from Ferriday after she graduated from high school in 1945.

THE LEGACY OF WILL HANEY

During the Soul Survivors Festival in Ferriday in 2012, the Mississippi Blues Trail dedicated a Blues Trail marker on the lawn of Ferriday’s Delta Music Museum in honor of Haney that includes a photograph of Haney’s Big House in flames.

Music writer Scott Barretta said Haney ultimately “provided a structured environment for the blues and helped the music flourish.”

Alex Thomas, Mississippi Blues Trail director, noted that Haney’s was part of the “Chitlin Circuit,” which provided “a stage for a who’s who of touring African-American musicians.”

Ferriday’s famous rock-n-roll great Jerry Lee Lewis “found out who was playing at Haney’s through the ‘Among the Colored’ column that appeared in the Concordia Sentinel in the 1940s and the 1950s.” Lewis told Billboard Magazine in 1958 that he and cousin Jimmy Swaggart, who became a famous evangelist, would listen outside on the sidewalk to the singers and the juke box. Then we’d run right home and try to play the same kind of great blues music.”

In an issue of the Sentinel in January 1950, Baretta found a note in that column that Frank ‘Cole Slaw’ Cully and his orchestra would be playing a return engagement at Haney’s. Other performers included B.B. King, Ray Charles, Little Milton, Roy Brown, Solomon Burke, Percy Mayfield, Big Joe Turner, Johnnie Taylor and Irma Thomas.

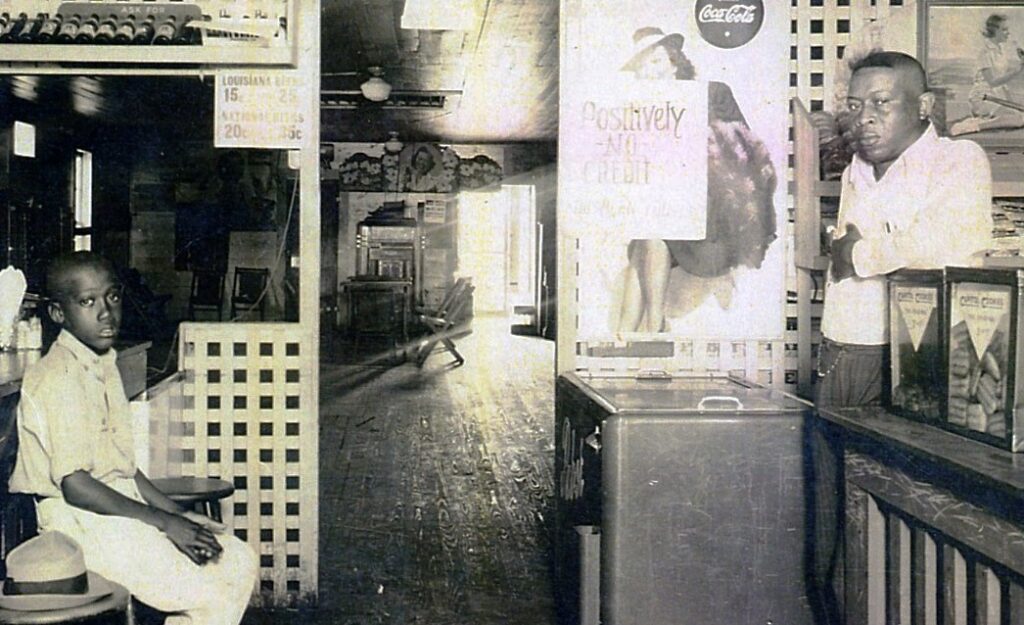

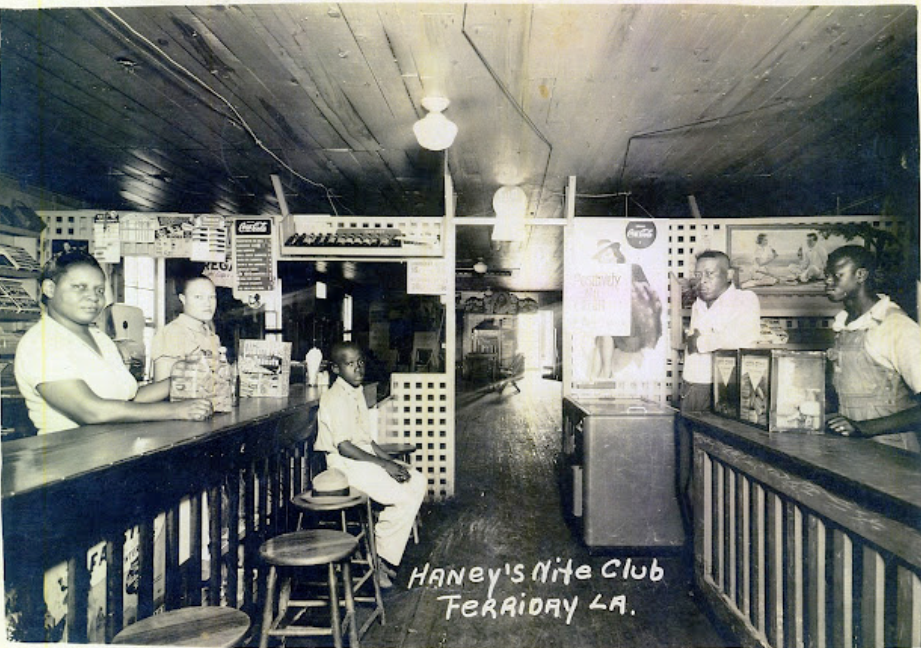

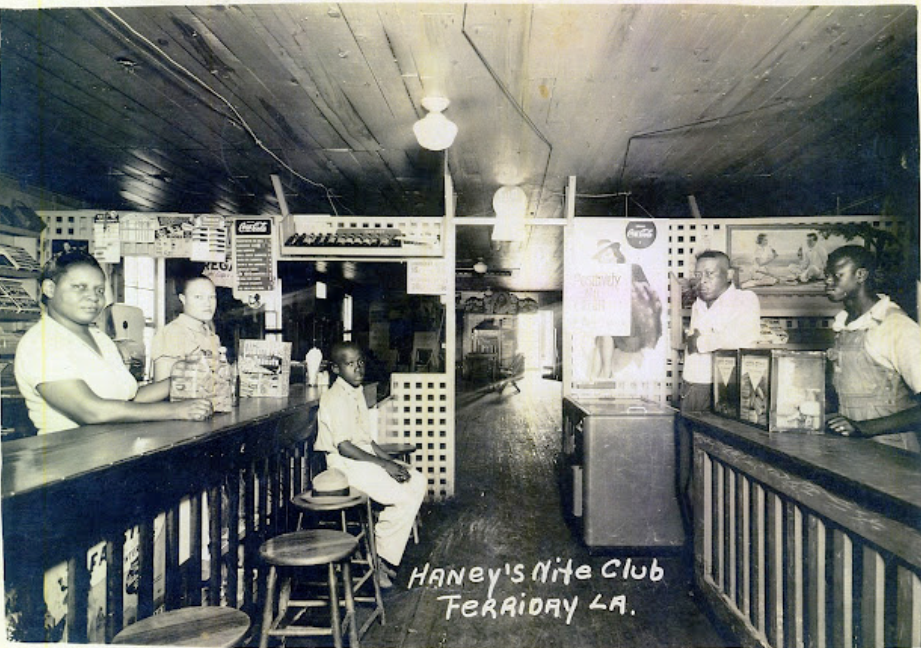

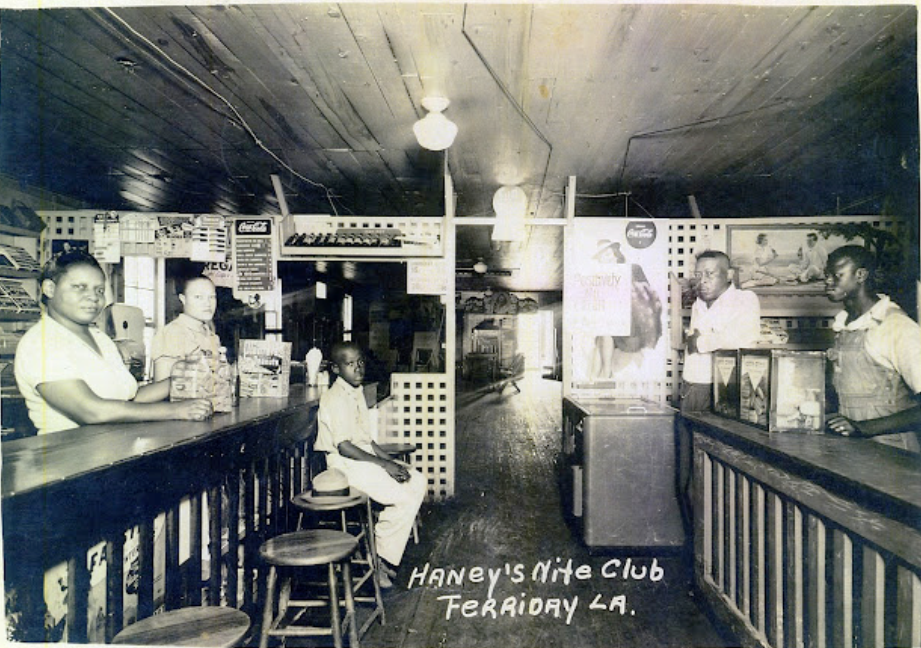

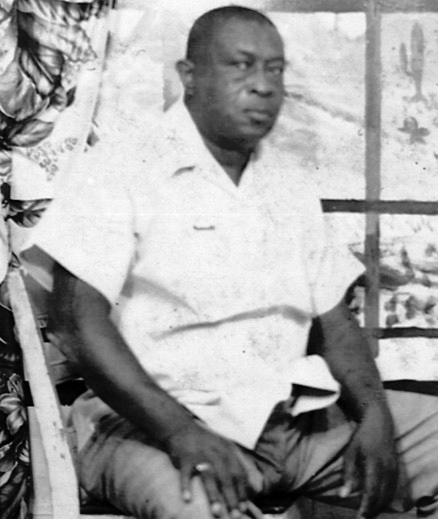

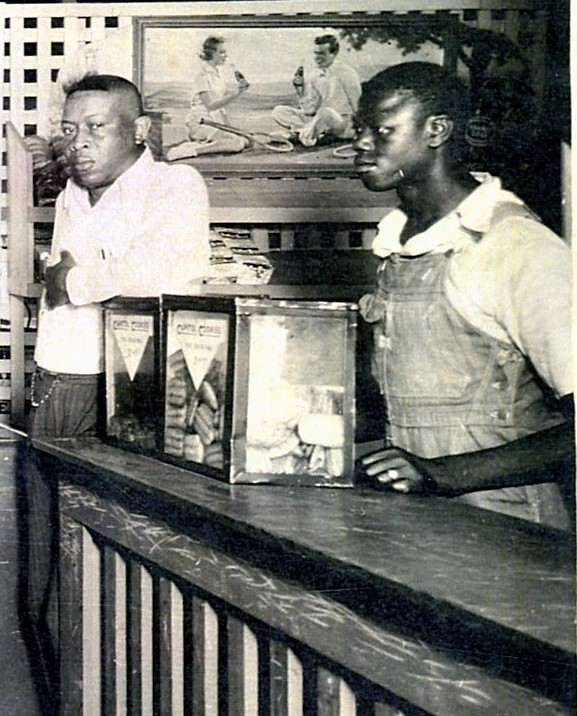

TWO PHOTOS OF HANEY INSIDE HIS CLUB

Father August Thompson, the Black priest at the St. Charles Catholic Church in Ferriday during the 1960s, was an amateur photographer. His photo of Haney’s Big House in flames in 1966 was the only known photo of the business. There were no known photos of the interior of the club.

For several years, the Concordia Sentinel ran articles in print and online soliciting photos of Haney’s. In 2010, a Houston, Tex., man, Gerald Williams, provided the newspaper two photographs of Haney and others inside the building.

Haney “was a close family friend of my great-uncle and grandmother when I was much younger in the ’50s,” Williams said. “These photographs were inadvertently handed down to me from them upon their deaths along with other family possessions.” Williams said his great-uncle Johnson Polk and grandmother Sophronia Polk Strother were both relatives of Haney and both originally from Vidalia.

Williams didn’t know who the other people in the photographs were and despite an effort by the Sentinel asking the public to help, no one came forward with information on the identities of the individuals pictured. One photo is labeled “Haney’s Big House, Ferriday La., 1956,” and shows Will Haney standing, four men sitting at the cafe counter, and two men sitting at tables in the background. The other picture, which is labeled “Haney’s Nite Club, Ferriday, La.” was likely taken a few years earlier and shows Haney along with employees and customers.

Music writer Baretta told the Concordia Sentinel that on “many of the projects for the Blues Trail, such as the marker in Ferriday, we conduct research about famous clubs that are remembered by thousands but it’s all too often that we can’t locate a single photograph. On the one hand, African American cultural expressions and institutions simply weren’t highly valued by those who controlled most newspapers, city libraries, historical societies, etc. during the segregation era. And, on the other hand, most of the people who attended Haney’s and similar nightclubs were working folks who likely didn’t own cameras.

“Locating photos like these helps considerably in efforts to correct the historical record to reflect the importance of institutions like Haney’s” and rescue it from “increasingly dim memories to something concrete and on par with those institutions that were better documented during their time.”

HANEY AND FRANK MORRIS

Haney and Ferriday shoe shop owner Frank Morris would become the two most prominent African-American businessmen in Concordia Parish. Both were also the only Black men to regularly advertise their businesses in the Concordia Sentinel.

Morris’ Ferriday shop, which opened in the 1930s, was located a block and a half north of Haney’s. Morris was 51 when his shop was torched by Ku Klux Klansmen in 1964 while he was still inside. He died four days later.

Haney was questioned by the FBI for information on Morris and on Joseph Edwards, a young Black man who went missing six months before Morris was murdered. Klansmen and police officers are believed responsible for the disappearance and apparent murder of Edwards. Haney recalled that Morris had long been one of his best friends. However, he told agents he didn’t know Edwards.

No one was ever arrested in either case.

The fire that destroyed Haney’s Big House in 1966 was attributed, according to reports in the Sentinel, to a “faulty ice machine.” Yet there was concern that the fire may have been started by the Klan. There also was speculation in the Black community that Haney may have been targeted because he had housed or planned to house civil rights workers in his motel.

Haney never rebuilt his famous nightclub. He died six years later in 1972 at the age of 76. He is buried in the Natchez National Cemetery (Section I, Site 70).

THE HANEY EXHIBIT

In 2024, the Delta Music Museum in Ferriday added an exhibit on Haney to honor his influence in the music world but also in recognition of his enormous success as a businessman in the Black community.

Museum Director Shaun Davis said the “exceptional story of Will Haney and the Big House is integral to the deep musical and cultural history of Ferriday, Louisiana, and the entire country. That history reaches far and wide in the creation of what would become Rock & Roll and Rockabilly music. Having the opportunity to witness first-hand the greatest musical stars of the day, in their prime, a young Jerry Lee Lewis credited Haney’s Big House with helping him discover his ‘musical mojo.’”

SOURCES

Census Records: 1900, 1930, 1950.

Paul Southworth Bliss, “Victory: History of the 805th Pioneer Infantry, American Expeditionary Forces,” 1919, St. Paul, MN.

Orue E. Ooley, “History of Company E,” 1919, St. Paul, MN.

Interview of James Watkins by Stanley Nelson, November 2007, Ferriday, LA.

Stanley Nelson, “Haney’s Big House – a legendary place – down the street from Morris’ shop,” Concordia Sentinel, November 26, 2007.

Stanley Nelson, “Half-century old photos capture Will Haney inside his famous Ferriday club,” Concordia Sentinel, December 8, 2010.

Stanley Nelson, “William Haney and Haney’s Big House,” 64 Parishes, March 31, 2021.

William Haney Draft Cards:

World War I, June 5, 1917, Vidalia, LA.

World War II, April 2, 1942, Ferriday, LA.

Haney’s Big House exhibit at Delta Music Museum in Ferriday, LA